Calvin, of Calvin and Hobbes, said it best: “Getting an inch of snow is like winning 10 cents in the lottery.” Everyone likes to win big. But what were the biggest winning storms—the all time huge dumps, and awesome events? And where did they happen?

I wanted to know. So I started digging around, and the biggest documented storm in world history dumped 189 inches—15.75 feet—on Mt. Shasta, California from February 13 to 19, 1959. Way back in 1959 there were no satellite images, no radar data and limited observations for the event. But, Hansen et al. (1) analyzed the storm in their 2013 paper and concluded that an event of this magnitude requires a number of key features to converge. “The timing and phasing of the northern and southern branches of the polar jet stream,” they wrote, “led to an idealized long-term juxtaposition of moisture and cold air.” Long-term mixing of moisture and cold air? I’d say so—it averaged more than 30 inches/day for six days.

On Thompson Pass, Alaska, the second deepest storm ever measured missed the record by a mere two inches, depositing 187 inches—15.6 feet—from Feb 19 to 25 in 1953. In the U.S., the single deepest documented day saw 75.8 inches at Silver Lake, Colorado. And, most can probably remember it: the most bountiful season on record happened at Mt. Baker during the winter of 1998-99, accumulating 1,140 inches of white—or 95 total feet (2).

The west coast of North America isn’t the only place that can pull together the required moisture and cold air. Japan enjoys consistently snowy winters thanks to cold air from Siberia that spills across the Sea of Japan, picking up moisture and dumping it on the Japanese Alps of Honshu Island, the main island. Burt (3), referencing the work of Fukui (4), estimates that at 2,000-6,000 feet in elevation, the Alps receive 1,200-1,500 inches per year on average—that’s 100 to 125 feet. The north island of Hokkaido gets its share, too.

What about remote areas of the Coast Range in B.C.? Or, southeast Alaska? How much snow falls in the snowiest spots of the Andes, or the South Island of New Zealand? The available data seems very limited and spotty, but I’m open to grant opportunities to research this. And, if I happen to hit it big in the snow lottery while researching, I’d be fine with a little skiing…all in the name of science.

STORMY PERSONALITIES: Four Types of Dumpers

Upslope

Lifting air cools, and, if cooled to its dew point, clouds and precipitation will form. An organized low pressure, with its counterclockwise rotation, can lift air thousands of feet by pushing it up the slope of the mountains. When a low-pressure system positions itself just south of the Beartooths, Bighorns or Front Range, the northeast or east flow can drop several feet of snow. These storms develop more often in March or April.

Lifting air cools, and, if cooled to its dew point, clouds and precipitation will form. An organized low pressure, with its counterclockwise rotation, can lift air thousands of feet by pushing it up the slope of the mountains. When a low-pressure system positions itself just south of the Beartooths, Bighorns or Front Range, the northeast or east flow can drop several feet of snow. These storms develop more often in March or April.

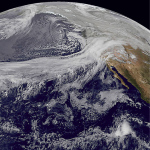

Pineapple Express

Big dumps require a steady stream of moisture. In a Pineapple Express, a strong branch of the jet stream transports a fire hose of moisture all the way from Hawaii, aiming it at targets—like the Coast Range or Cascades—on the West Coast. Low elevations can be flooded while upper elevations get dumped. But, it’s a warm flow, so you might be cursing the “R” word to rather high elevations.

Big dumps require a steady stream of moisture. In a Pineapple Express, a strong branch of the jet stream transports a fire hose of moisture all the way from Hawaii, aiming it at targets—like the Coast Range or Cascades—on the West Coast. Low elevations can be flooded while upper elevations get dumped. But, it’s a warm flow, so you might be cursing the “R” word to rather high elevations.

Lake Effect

Lake effect snows form when cold air moves over warmer water. The interaction adds moisture and heat to the air mass, lifting it. When the topography downwind of the lake lifts it further, intense plumes of snowfall result. The classic snow belts downwind of the Great Lakes owe their snow to this effect, and Wasatch snowfalls get a boost from the Great Salt Lake. The same phenomenon happens over the Sea of Japan, resulting in sea-effect snow.

Lake effect snows form when cold air moves over warmer water. The interaction adds moisture and heat to the air mass, lifting it. When the topography downwind of the lake lifts it further, intense plumes of snowfall result. The classic snow belts downwind of the Great Lakes owe their snow to this effect, and Wasatch snowfalls get a boost from the Great Salt Lake. The same phenomenon happens over the Sea of Japan, resulting in sea-effect snow.

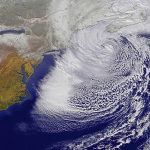

Nor’easter

A nor’easter forms when a well-developed low moves northeast along the East Coast. It’s named after its northeast winds on land caused by the counterclockwise rotation around the center that’s positioned just offshore. It can form as far south as the Gulf of Mexico, and the clash between an Arctic blast and warm Gulf air fuel the storm with energy and moisture. A single storm can dump feet of snow from the mountains of North Carolina all the way to Atlantic Canada.

A nor’easter forms when a well-developed low moves northeast along the East Coast. It’s named after its northeast winds on land caused by the counterclockwise rotation around the center that’s positioned just offshore. It can form as far south as the Gulf of Mexico, and the clash between an Arctic blast and warm Gulf air fuel the storm with energy and moisture. A single storm can dump feet of snow from the mountains of North Carolina all the way to Atlantic Canada.

(1) Cassandra Hansen, Michael L. Kaplan, Scott A. Mensing, S. Jeffrey Underwood, John M. Lewis, K. C. King, and Jake E. Haugland, 2013, They Just Don’t Make Storms Like This One Anymore: Analyzing the Anomalous Record Snowfall Event of 1959, J. of Operational Meteorology, Vol. 1, No. 5.

(2) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Climatic Data Center, Existing Records, www.ncdc.noaa.gov/extremes/ncec/records.

(3) Christopher Burt, 2012, www.wunderground.com

(4) Eiichiro Fukui, 1977, The Climate of Japan, Kodansha.

This story first appeared in the January issue of Backcountry Magazine.

Related posts: