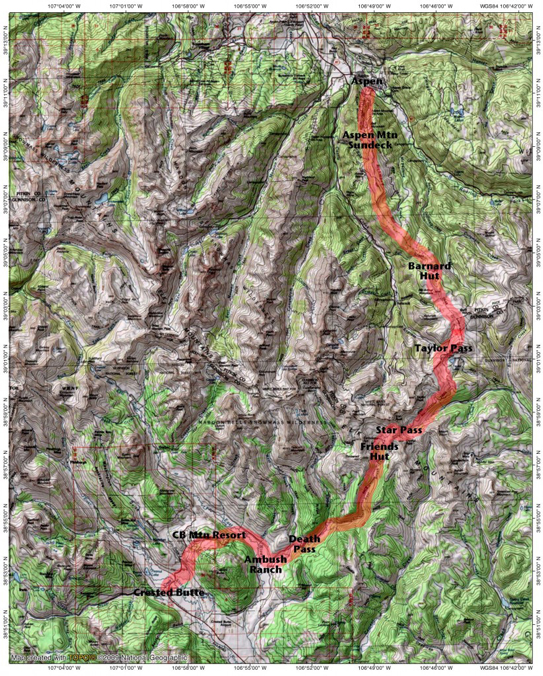

This past weekend marked the 18th Elk Mountain Grand Traverse, a 40-mile backcountry ski race between Crested Butte and Aspen, Colo. The race kicks off at midnight, and racers generally finish between eight and 16 hours—if they make it to Aspen at all. Across those long miles, racers must traverse over 7,800 feet of elevation gain, transition from skins to skis and back again and encounter whiteouts, stream crossings and more. Here’s the account of one 2015 Grand Traverse racer, Lydia Tanner.

It’s been two days since the Elk Mountain Grand Traverse, and I’m finally tasting food again. As in, actually noticing what I put in my mouth, rather than just the quantity available. The famous backcountry test-piece covers 40 high-altitude miles, 25 of which we never saw—but I’ll get to that in a bit.

It starts at midnight. Mount Crested Butte is floodlighted for the occasion, but the stars could do the job just as well. Behind us is a hooting crowd, and beyond the reach of our clustered headlamps is the long walk to Aspen. Someone is making a speech over a loudspeaker, but all I can catch is a faint “may ye skin wax be not clumpy….” Everyone’s had half of the night to get good and nervous. My partner and I exchange excited grins.

After a moment that is both infinitely long and far too short, someone starts a countdown and we go. The rando racers surge up the hill like freed fireflies, leaving the less spandex-inclined to wonder about our glide as we search frantically for open snow to plant a pole. Five minutes in and I’m anaerobic; ten and I’m tasting blood. The lights behind us dwindle as the race stretches uphill.

The first transition is full-on carnage, with fallen skiers strewn about the icy descent. As we round a corner into a gully, I’m grateful for my heavy metal edges. After a river crossing that involves one racer chasing a rogue ski almost into a barbed wire fence, things finally string out. I look back to see the way lit by a strand of lights and the rising moon. I’ve never seen anything so eerie or beautiful.

Volunteers have lit bonfires along the way, and we call out our numbers and thank-you’s as we shuffle through the warmth back into the dark. It’s surreal and chaotic, with long stretches through the sage followed by spicy descents into half-frozen rivers. We shoulder our skis, we clip them back on, we put our heads down and kick-glide, kick-glide. I’m filled with admiration for the hardmen of yesteryear, who carried mail between Aspen and Crested Butte via the same route. I’m also beginning to resent those heavy metal edges.

Then I shear the top buckle off my boot postholing. Another racer immediately offers me her voile strap, but I’ve got one; it’ll be another ten miles before I need it to descend, anyway. I yank the traitor piece off my boot, pocket it and keep moving.

What I don’t know as we work our way through every fallen log, moonlit field and muddy bootpack is that we won’t make it to the descent. I manage to down just 300 nauseating calories over six hours, and by the time we reach our first major checkpoint, Friends Hut, I’m so far gone that I can barely keep a sip of water down. My partner isn’t doing much better. Somehow we hadn’t planned on rebellious midnight bellies.

The sun is rising over Star Pass, but we can’t feel anything but hypoglycemic dread as we gaze towards the saddle. People trickle through the checkpoint in varying states of pain, and we agonize over the decision. Eventually, pathetically, we bail.

Here’s where I have to zoom out, because it’s where I cried. We had friends and family members who’d woken up in the middle of the night to watch our spot beacon progress across a digital map. We’d given up a winter’s worth of powder days and climbing trips to train, and we’d failed.

As we hacked our way back to the bail-point, we had to sit down every twenty minutes or so to rekindle enough energy to keep moving. We managed to split one more bar and down a little more water, but our stomachs were rejecting everything. By the time we slid to a stop next to a truck full of happy dogs and a nice guy waiting to take us back to Crested Butte, we’d been out for 30 miles and 11 hours.

These days we tweet our victories but rarely our failures. People accomplish amazing things and we hear about them both constantly and exclusively, which makes it difficult to remember that for every summit there are lots of people who try really hard and don’t quite make it.

Yet there’s something cathartic about getting spanked in the mountains. We quickly learned that we weren’t prepared for this trip, but I’m grateful for the lesson. I’m not sure how I feel about training (really training) for skiing, but I know I’ll be back, someday, and I’ll be ready.

Related posts: