Warm winters and below-average snow totals have brought the issue of climate change to the forefront of many backcountry skiers’ minds, but understanding its impacts and how to pursue solutions can be overwhelming. To make this issue more tangible, University of Vermont alums Isabelle La Motte and Micah Berman have turned to video to tell the climate story and inspire people to action. This November, they premier Last Tracks, a solutions-oriented film project that spreads a message of urgency but also empowerment.

We caught up with La Motte and Berman to hear more about their video project and their thoughts on climate change. Here is what they had to say.

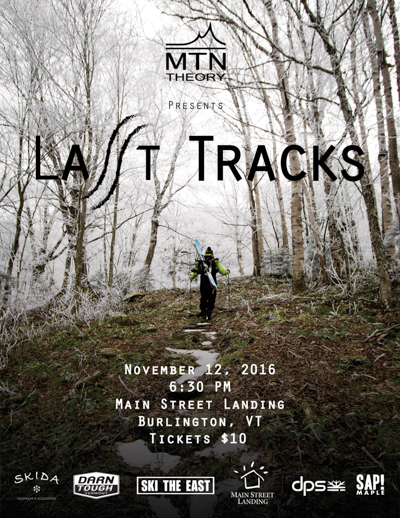

Last Tracks premiers in Burlington, VT on November 12th, 2016

Backcountry Magazine: What was the process you went through in producing Last Tracks?

Micah Berman: We’ve had the idea for three years, and have been actively working on the film for two years. We came up with the idea after interning for T-Bar Films and we wanted to make something of our own. We both like making ski movies, but being environmental majors [at UVM], we wanted to put an environmental spin on a ski movie and see where that goes. So we did a Kickstarter with a goal of [raising] $5,000 dollars. We ended up raising almost $6,000 for the film, and that really got the ball rolling. So we figured out the film equipment we would need, the places we would shoot and went from there.

Isabelle La Motte: We filmed two winters ago, and we didn’t have a clear plan, but after the season was over we were not nearly where we wanted to be with the film. So, this past season we really cranked down on the project. Last summer we took the time to sit down and write out a script. We found people to play the characters we wanted and brainstormed who we wanted to interview. We spent this winter committing all of our time to filming, and we spent this summer and fall editing the film. We’ve been living and breathing this movie for the past year.

Morning light filming in Vermont’s Bolton backcountry [photo] Micah Berman

ILM: I’ve thought about this issue for awhile. Are people actually thinking about climate change? Or, did I go to UVM and live in this bubble for four years where that is what people talked about? I think either way, it’s important to take what we learned at UVM and make climate change a more talked about issue. We think it needs to be at the forefront for the ski industry, politics and just general conversation. The idea of climate change can be super overwhelming when presented on a global scale, so we wanted to hit a direct target audience—one that we are a part of, one that we could connect with—and say, “Hey! Climate change is affecting you directly in this way—in this one part of your life—and you can focus on that one part and try and make a difference.” We are trying to make it more accessible instead of trying to tackle climate change as a whole, because that can scare people.

MB: We are at a very crucial time, particularly for skiers. [Skiing] is one of the first sports, lifestyles and communities that is going to see real change. With skiing it’s like, “Oh yeah, we don’t have enough snow. It’s not cold enough to blow snow, we can’t open this year.” It seems like a thermometer for climate change. Once skiing goes, then we know [the problem is] a lot bigger.

BCM: Do you think the ski industry is going to be resilient in the face of climate change?

ILM: Yeah, Mad River is typically open for 100 days during the ski season, and last season they were open for 45.

MB: I think the hard part for some people to grapple with is that some years can be terrible like last year in the East, and this year we might have above average snowfall. I think the biggest point that people need to realize is that climate change doesn’t necessarily mean that the world is going to get warmer in any given year. It is an average measurement, and what happens is storms and other weather events become more sporadic and more random. We are going to see these ridiculous events more often.

BCM: How do you think “natural” ski areas like Mad River will be affected by climate change?

ILM: Eighty-eight percent of ski areas rely on snowmaking, and Mad River obviously isn’t one of those; they are definitely [a resort] to watch to see what happens. My dad works at Magic Mountain in Southern Vermont, and they are a small area that can’t afford what the big areas can produce snowmaking-wise. What happens to them? They are not going to afford to be able to stay open, which is awful to think about.

BCM: Climate change can be a doom-and-gloom subject. Does Last Tracks have any positive messages, or offer any solutions for the ski community?

ILM: That was a huge thing from the beginning that we’ve been thinking about. How do we not leave people after they see this movie thinking, “Oh, skiing is going to be over forever.” We want people to leave thinking, “Alright, we are still at a point where we can do something, and I can have an impact.”

At the end of the movie we do leave people with the message, “Go out and do something, take action, it’s not too late, we can still have an impact in this fight.”

MB: We talk about what is happening. We talk about where we stand in the ski community. Then, for the last half of the movie, we focus on what we still have the ability to do in 2016. We offer multiple ways of how you can have an impact.

ILM: And, that skiers have the responsibility to [take action].

BCM: I know you filmed in Vermont. You also filmed in Little Cottonwood Canyon. Did you film anywhere else for Last Tracks?

MB: It was primarily in Vermont, secondarily in Utah, and then we filmed at Tuckerman’s Ravine in New Hampshire for a couple days.

Elliott Casper smiles his way up the boot pack on location in Utah [photo] Micah Berman

MB: The way we approached this was less from a scientific, Inconvenient Truth standpoint, and more from a recreational standpoint. I think that [a recreational view] can appeal to people who are indecisive about the issue, or to people who don’t believe in it. We are approaching climate change from a fairly neutral standpoint of, “This is what is happening, you can choose to ignore it if you want, but it is pretty clear that there is something going on.” We need to work to actually figure out what’s happening and how to combat it or mitigate it.

ILM: We are trying to bring the community together. We are not shoving facts and numbers down people’s throats. We didn’t want people to be zoning out—we are trying to unite people, to get that passion going. Skiers are the most passionate people that I’ve met in my entire life, whether it is about skiing or something else. They just have that drive, and we want to spark that passion.

BCM: Why did you choose Burlington as the premier location, and where else can viewers expect to see the film this fall and winter?

ILM: We chose Burlington, because Micah and I both recently graduated from UVM. Most of our Kickstarter support came from the East Coast. We wanted to make sure [East Coasters] had access to the premier, because we owe that to them. Also, just being in Burlington—the film fits there—we wanted that community to be able to see it.

MB: I’m from New Hampshire. We’re also planning to show it in the Dartmouth area and in the Mt. Washington Valley. We are not really sure where we will bring it in December; hopefully the Boston area. We will be heading to Crested Butte in January, and plan to have a showing here, and then see what venues we can reach out to.

ILM: Telluride, Denver, Salt Lake.

Behind the scenes while filming Last Tracks [photo] Isabelle La Motte

MB: Here’s one story in terms of backcountry, which aligns with what you guys [Backcountry Magazine] do. In the film, we talked to a someone that is involved politically and works with the state government for forestry regulations. He is also an avid backcountry skier. He shines a light on how to promote skiing in the backcountry, finding your own way in the wilderness and connecting to skiing. He explains how we can still recreate in the backcountry and how we can plan and manage [our landscapes] for the future.

—

Last Tracks premiers in Burlington, Vermont on November 12th. For more information, visit Mountain Theory Films.

Related posts: