Colorado’s Bluebird Backcountry is a fully human-powered ski area, complete with rentals, instruction, guiding and lodges and devoid of chairlifts. In a time of uncertainty and change within the ski resort business, this model, and variations of it, may be the clearest way forward.

Three brightly-colored-puffy-clad skiers walk into a saloon. On any other night, we may have been met by clichéd stares from the bearded men who line the tables, perhaps with a tumbleweed skittering across the floorboards. But it’s Thursday, which means one thing in Kremmling, Colorado, a 1,450-person town on the road between Denver and Steamboat Springs: trivia night at the Grand Old West bar. While I try to return a few sideways glances with a smile and a nod, most folks’ attention focuses on the woman at the back of the bar as she hollers off answers to the game’s latest round.

After my second day of skiing at Bluebird Backcountry, a new ski area concept that lies about 30 miles north of town at the eastern flanks of Rabbit Ears Pass, I’m ready to kick back alongside the resort’s cofounders, Erik Lambert and Jeff Woodward. It’s early March, but the sunny day had felt more like May.

We’d toured around their softly contoured terrain, taking laps up the set skintracks and down through open slopes and aspen groves. Between runs, we paused at the Perch Warming Hut, a 20-minute skin from the parking lot and base area, to snag some of the bacon and burgers a staff member was cooking on a small, outdoor grill. It’d been a good, simple day.

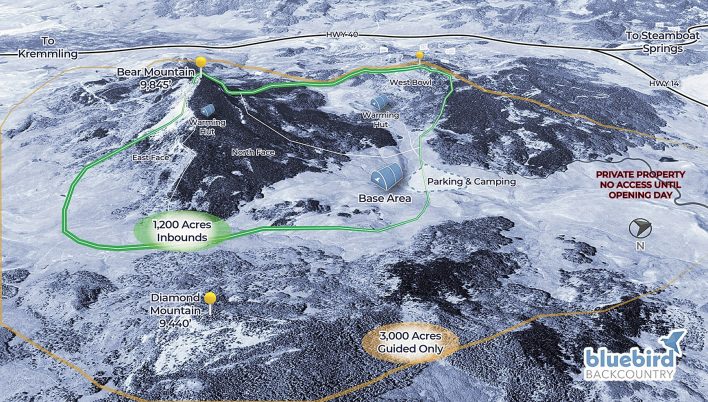

Simple, however, doesn’t mean run-of-the-mill. Lambert and Woodward are winding down their inaugural season at their first-of-its-kind, entirely human-powered ski area. Located on land leased from Peak Ranch, a 50,000-acre cattle ranch, Bluebird offers most of the conventional ski-area amenities—equipment rentals, lessons, guided tours, base-area infrastructure—and no chairlifts. During the first season, which ran from February 15 to March 15, their terrain encompassed 1,600 acres, 500 of which were patrolled (and they call “inbounds”) and the remaining 1,100 accessible only with a guide. While Bluebird doesn’t bomb to control for avalanches, the ski patrol team assesses the rolling, mostly low-angle hills each morning, evaluating the snowpack to determine if any particular slopes should be closed. Lambert and Woodward’s goal is to mitigate some of the barriers to entry to getting into the backcountry, like equipment costs and avalanche knowledge, to provide more introductory opportunities.

“The idea came to me while I was taking my brother out to backcountry ski,” Woodward told me the night before, as we stood around a small campfire beside some cabins on the edge of Kremmling. “He was just learning, and I realized how dangerous and expensive it could be. I was like, ‘There has to be an easier way to learn.’”

In 2018, Woodward and Lambert conducted a survey to gauge interest in a learning-centered, chairlift-free resort, and after receiving over 3,000 responses that largely voiced positive and supportive feedback, they assembled a team to plan and develop their concept.

By April 2019, Lambert and Woodward had set up two trial runs: one on Colorado’s Mosquito Pass and the other at Winter Park Resort after it had been partially closed toward the end of the season. Over six days, Bluebird hosted approximately 170 guests and used the opportunity to understand skiers’ interest in lessons and the amount they were willing to pay for the experience.

Then, one of Lambert and Woodward’s volunteers mentioned a connection—their dad’s cousin owned a cattle ranch just outside of Kremmling, and, if there weren’t too many headaches involved, he’d be open to leasing some acreage that is too snowy for grazing in the winter. The two jumped at the offer and set up a Kickstarter to raise money for a base lodge and mid-mountain warming tent, as well as to fund a paid patroller position.

By the time I was eating bacon at the warming tent during Bluebird’s month-long opening, Lambert and Woodward had raised $107,000 from 1,000 backers, who, depending on the amount of their donation, received Bluebird schwag, day passes or, for those who chipped in over $950, a privately guided day. For Lambert, their crowdfunding success lies in the appeal of their mission, which focuses on providing education and access.

“We’re building programs for beginners, intermediates and experts,” he explained earlier that day in the base lodge, a cozy, permanent structure with a round roof and AstroTurf floor. “The first thing you learn in your lesson is that you’re not really ready to go into the backcountry. So we try to instill backcountry habits, even though they’re not necessarily necessary in controlled terrain. We focus on skiing in pitches, beacon checks, making sure you work with your partners.”

“Backcountry skiing is growing,” he continued. “I think people are looking to avoid the ‘industry’ of skiing—parking problems, gondolas—they’re ready to learn something new. But taking an avalanche course and hiring a guide can be a big leap. We focus on meeting one another, finding mentors and learning in a place that’s safe and controlled.

LEARNING TO BACKCOUNTRY SKI AND RIDE in such a controlled environment—with access to mentors, lessons, ski partners and rental equipment, including touring setups and avalanche gear—is about as smooth of a transition as one could hope for. And, with increased interest in the sport, Bluebird’s timing and pricing—a day ticket costs $50—couldn’t be better.

For the past decade the population of backcountry skiers and riders has been steadily rising, and, most recently, that number jumped exponentially—from a reported 1.4 million users in the 2017/18 season, according to SnowSports Industry of America (SIA), to SIA’s reported 6 million today. Add in surging equipment sales in 2020, an outcome of last spring’s early resort shutdowns and this season’s unpredictability related to Covid-19, and the need for education and an easy backcountry introduction is more relevant than ever.

More broadly, corporatization is sweeping across the resort business, with companies like Vail and Alterra together now owning more 50 resorts globally. Along with such a shift, the cost of skiing at resorts has skyrocketed—a day ticket at Vail, Colorado, for example, costs $209—and coop pass models, like the Epic and Ikon passes, are widely considered to be further driving resort crowding. Factor in the reservation systems being implemented by most major ski areas due to Covid-19 regulations, and smaller, independently owned operations stand in sharp contrast.

Bluebird similarly requires a reservation system, limiting the total number of guests per day to 200 and for the purpose of reserving guides, lessons and rentals and for signing up for avalanche courses. But their vibe focuses on building community, and their model seeks to promote accessibility. And they’re not the only ski area focusing on these values and looking to bring the backcountry into their offerings.

WHILE VERMONT’S BOLTON VALLEY RESORT is far from entirely human-powered—they have six chairlifts—their backcountry terrain encompasses 12,000 acres of trails and glades that are adjacent to the 45,000-acre Mt. Mansfield State Forest. The resort’s backcountry program is entering its fourth year and, like Bluebird, offers lessons, rental touring setups, a backcountry warming tent and guided tours. Within their menu of courses, the introductory-focused ones have seen the most traffic.

“Our most popular program last year was a private intro clinic followed by a half-day tour,” says Adam DesLauriers, Bolton’s backcountry programs director. “That seems to be our go-to product that people are looking for. We’re sort of a gateway for backcountry skiing for a lot of people. They want to check out the equipment, be shown around and practice with the gear—get the miles in so they can do some exploring on their own.”

While Bolton has offered daily equipment rentals before, this is their first year providing season-long offerings, including 40 AT and 20 splitboard setups. “We were playing with the idea of season rentals before, but this year is a slam dunk,” DesLauriers says, noting that those rentals were completely sold out by late October. “People are bumping up against a lack of product in the retail shops; they’re selling out and nobody’s got any product. We sold all of our daily rental fleet in a heartbeat last year.”

The speed with which classes and equipment have sold is encouraging for DesLauriers, but it comes with a few catches, including making sure people actually pay to access their trails and terrain. To address those concerns, the resort has created a Nordic, Backcountry and Uphill (NBU) Pass, which, like its name implies, gives skiers and riders access to the cross country and backcountry trails, as well as uphill routes on the alpine trails, and includes three one-ride lift tickets. That NBU Pass costs $190—roughly a quarter the cost of an alpine pass—and a day ticket runs $17.

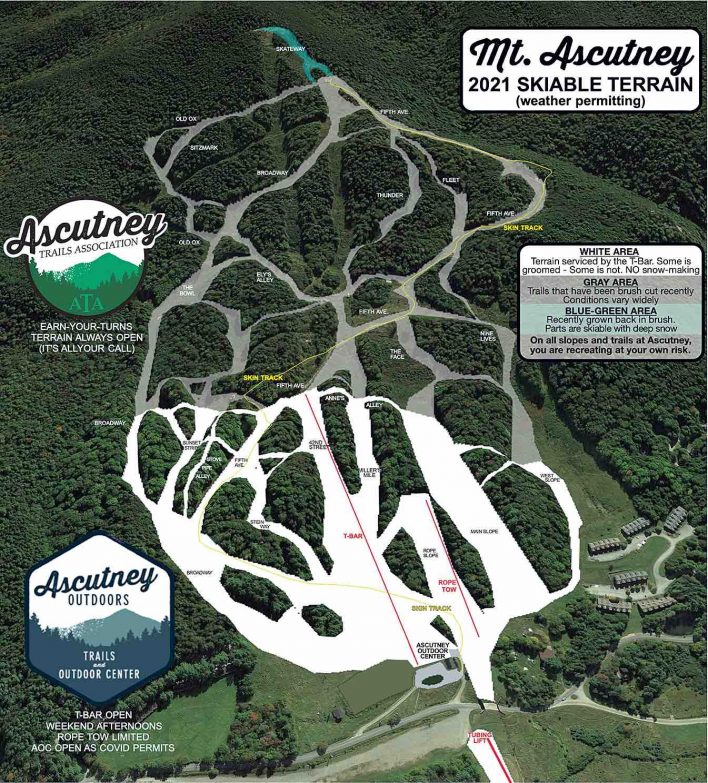

Farther south in the state, Ascutney Outdoors is taking a similar approach. The nonprofit has been managing the former Ascutney Mountain Resort, which the town of West Windsor purchased in 2014 after the resort stopped spinning its lifts in 2010. Now, Ascutney Outdoors maintains the mountain’s upper alpine trails for the public to tour on and has erected a T-bar and rope tow on the lower portion of the mountain; for lift access, they sell a $100 “supporter pass” or an adult day ticket for $15. A 3,500-square-foot Outdoor Center, which replaces the original base lodge that burned down in 2017, serves as a community event space, the main trailhead for mountain bike trails and a lodge and warming hut in the ski season. Aside from the Outdoor Center, T-bar and rope tow, the mountain features no other infrastructure, guiding, lessons or rentals.

“We’re well aware of the increasing interest in backcountry skiing, and the upper trails not served by the T-bar are very popular for those who like to earn their turns,” says Glenn Seward, the executive director of Ascutney Outdoors. “We’ve made a real effort to make all of the trails that aren’t lift served open for backcountry skiing. We allowed some to regenerate, but we’ve kept many open.”

Like at Bolton and Bluebird, Ascutney Outdoors is preparing for an uptick in skiers and riders this season due to the impact of Covid-19—an expected trend across these backcountry-oriented ski areas as more traditional resorts require reservations to control crowding. Unique to Ascutney, there’s no charge to access the trails—there’s the supporter pass for those looking to contribute to the nonprofit or use the rope tow or T-bar, but human-powered movement is free. “You pull into the parking lot, strap your gear on and go,” Seward says. As for rental equipment and guiding services? “Everyone’s on their own,” he continues. “We provide a map.”

Ascutney’s community-focused model is unique to its circumstances—centered on a defunct ski-resort-turned-backcountry-zone. But in many senses, it’s similar to Colorado’s Silverton Mountain Ski Area, which since 2002 has offered a low-frills skiing experience in the San Juan Mountains. Both focus on accessibility and, compared to other resorts, are more affordable. The difference? While Ascutney offers mellow skiing in Vermont’s Green Mountains, Silverton is known for its staggeringly steep and avalanche-prone slopes that can be accessed via their lone chairlift, helicopter or touring.

“When we started [Silverton] our focus was on the niche that we thought were being abandoned by a lot of ski resorts trying to be all things to all people,” says Jen Brill, who founded Silverton with her husband, Aaron. “Those expert and advanced skiers.” The Brills focused their resort around that single chairlift and heli access to 22,000 acres of Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land that runs adjacent to the resort boundaries. It presented the opportunity for skiers and riders to explore backcountry terrain in a guided, resort-like setting. And a guided full day at Silverton still costs less than a full-day ticket at Vail or Vermont’s Stowe Mountain Resort, at $189.

“You could be an advanced skier but someone who’s a resort skier and who doesn’t know if it’s worth the budget or if they’re at the physical-ability level that they need to be,” Brill says, “and you can come get an idea along our ridgeline.” Silverton’s model is largely based around guiding, but unlike Bolton or Bluebird, there’s no green-circle touring terrain. Instead, Silverton caters to the expert resort skier or rider looking to get off piste in a structured environment.

“We start at Silverton Mountain by telling people that you could die here today,” Brill says. “We tell them to wear beacon, shovel, probe, and we hit them pretty hard with the [message of] ‘be aware of where you are.’ We tell people the seriousness of the backcountry, even though it is in a guided environment.”

For Brill, Silverton will never cater to beginner skiers—it’s neither part of their model nor does their terrain support it. But there’s common ground in the hybrid backcountry/inbounds offering of Silverton, Bolton, Bluebird, Ascutney and similar ski areas. Each focuses more on the skiing than the amenities, the condos or the catered base lodges, each is a more affordable and accessible way to ski, and each demonstrates a way forward for the kind of skiing and riding experience that really matters in a time when ski resorts are rife with uncertainty and change.

BACK AT KREMMLING’S GRAND OLD WEST, Woodward returns to a talking point he’d mentioned earlier that day, while we transitioned atop one of Bluebird’s knolls: the possibility of acquiring a new zone to use for the following season. He’d pointed to the potential new spot, across US-40 from where we stood, a steeper sloped and treed area that appeared to be only a few miles away.

“It would have a lot more acreage for guided tours and inbounds skiing, and it gets way more snow,” he explains, with a smile and shrug.

As luck and hard work would have it, I’d later learn, Bluebird was able to move to that new location, Bear Mountain, also owned by Peak Ranch, for this season. Their patrolled terrain has nearly tripled in size to 1,200 acres and guided terrain now totals 3,000 acres. In a year expected to have record-high numbers of backcountry users, this means more room for increased traffic, for beginners on their first backcountry lesson and, maybe, for their new ski area model to gain traction elsewhere.

This article was originally published in Issue #137. To read more, pick up your copy at BackcountryMagazine.com/137 or subscribe.

Related posts: