For 29 years, Doug Chabot worked as a forecaster for Montana’s Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center. In this Wisdom piece from The Outliers Issue, available now, he shares a few nuggets of wisdom.

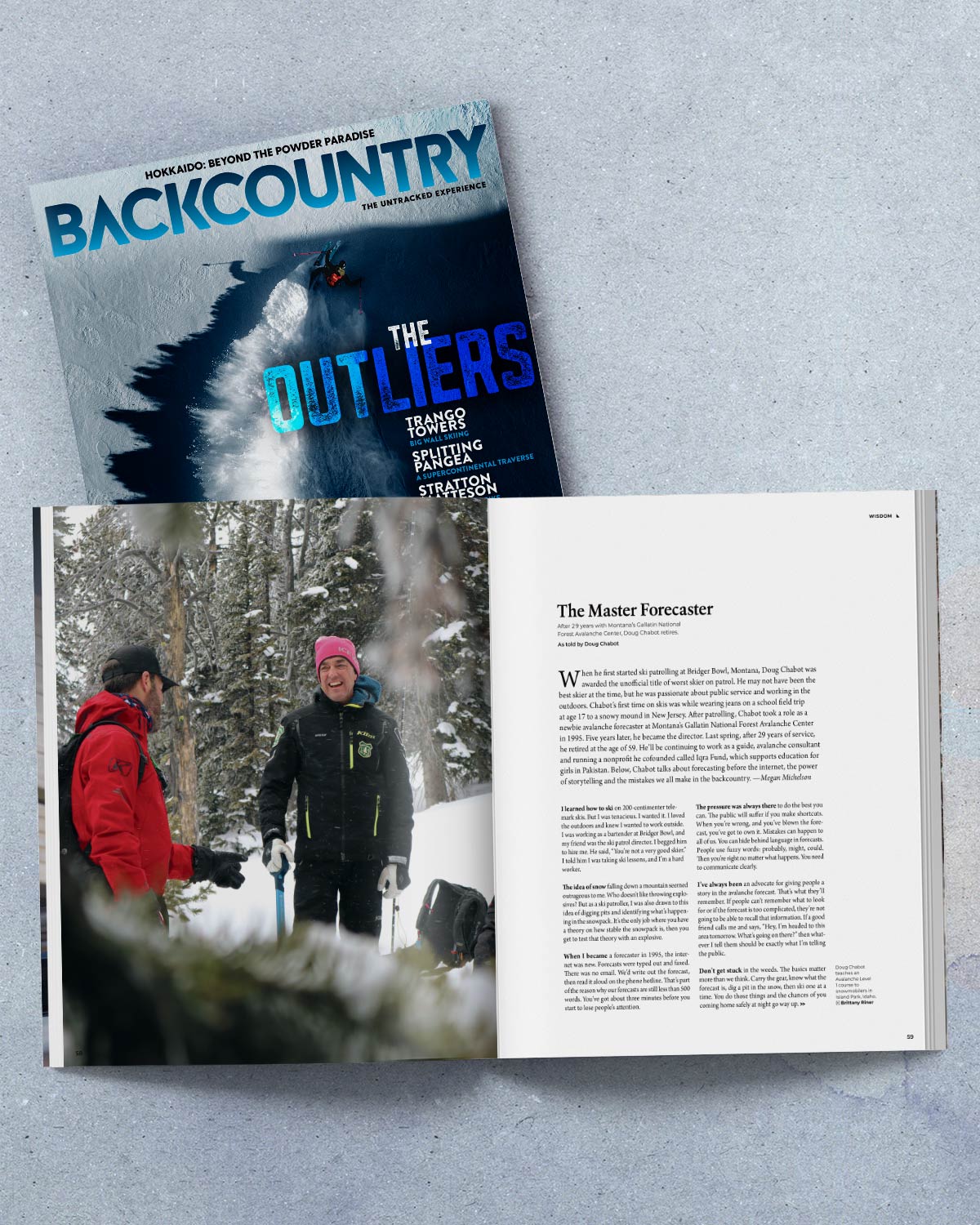

When he first started ski patrolling at Bridger Bowl, Montana, Doug Chabot was awarded the unofficial title of worst skier on patrol. He may not have been the best skier at the time, but he was passionate about public service and working in the outdoors. Chabot’s first time on skis was while wearing jeans on a school field trip at age 17 to a snowy mound in New Jersey. After patrolling, Chabot took a role as a newbie avalanche forecaster at Montana’s Gallatin National Forest Avalanche Center in 1995. Five years later, he became the director. Last spring, after 29 years of service, he retired at the age of 59. He’ll be continuing to work as a guide, avalanche consultant and running a nonprofit he cofounded called Iqra Fund, which supports education for girls in Pakistan. Below, Chabot talks about forecasting before the internet, the power of storytelling and the mistakes we all make in the backcountry. —Megan Michelson

I learned how to ski on 200-centimenter telemark skis. But I was tenacious. I wanted it. I loved the outdoors and knew I wanted to work outside. I was working as a bartender at Bridger Bowl, and my friend was the ski patrol director. I begged him to hire me. He said, “You’re not a very good skier.” I told him I was taking ski lessons, and I’m a hard worker.

The idea of snow falling down a mountain seemed outrageous to me. Who doesn’t like throwing explosives? But as a ski patroller, I was also drawn to this idea of digging pits and identifying what’s happening in the snowpack. It’s the only job where you have a theory on how stable the snowpack is, then you get to test that theory with an explosive.

When I became a forecaster in 1995, the internet was new. Forecasts were typed out and faxed. There was no email. We’d write out the forecast, then read it aloud on the phone hotline. That’s part of the reason why our forecasts are still less than 500 words. You’ve got about three minutes before you start to lose people’s attention.

The pressure was always there to do the best you can. The public will suffer if you make shortcuts. When you’re wrong, and you’ve blown the forecast, you’ve got to own it. Mistakes can happen to all of us. You can hide behind language in forecasts. People use fuzzy words: probably, might, could. Then you’re right no matter what happens. You need to communicate clearly.

I’ve always been an advocate for giving people a story in the avalanche forecast. That’s what they’ll remember. If people can’t remember what to look for or if the forecast is too complicated, they’re not going to be able to recall that information. If a good friend calls me and says, “Hey, I’m headed to this area tomorrow. What’s going on there?” then whatever I tell them should be exactly what I’m telling the public.

Don’t get stuck in the weeds. The basics matter more than we think. Carry the gear, know what the forecast is, dig a pit in the snow, then ski one at a time. You do those things and the chances of you coming home safely at night go way up.

“I’ve always been an advocate for giving people a story in the avalanche forecast. That’s what they’ll remember.”

In my career, 54 people died in avalanches in southwest Montana. That’s a big number. When there’s been an accident, the first thing you do as a forecaster is you go back and read the forecast. Did I communicate in an effective way what the problem was? In most cases, the answer is yes. Not everyone follows our advice, not everyone reads the avalanche forecast. And even if they read it or follow our advice, not everyone makes the best decisions, and sometimes, no matter what, bad luck strikes.

Avalanches happen because of what’s happening inside the snowpack. So, if you’re not looking inside the snowpack, you’re missing a huge piece of why an avalanche might occur. Why be blind if we don’t need to be? You don’t have to dig a pit every time you go, but putting your shovel in the snow can help answer the question of whether or not you should put your life on the line.

People think they’re skiing one at a time when they’re not. We mean that literally: One person goes, and when they’re all the way done, done, done, then you go. It’s not one person goes, you count until 15, then you go. This is how we often end up with multiple people caught in slides.

You’ve got an 80% chance of digging someone out alive if it’s done within 10 minutes. In the heat of battle, if your partner gets caught in an avalanche, you’ve got to get to them, then get them out. Ten minutes isn’t much. The only way you’re going to do that is if you practice.

Forget the danger rating—it leads to complacency. People put too much emphasis on a danger rating and a color instead of asking the real questions. Have there been recent avalanches? Where is the weak layer? What’s the weak layer that’s going to break? We always say just because it’s low danger that doesn’t mean it’s no danger.

Now that I’m done forecasting, I’m really looking forward to not having to carry around a heavy pack. I used to have to haul around communication gear, first aid, emergency stuff. On top of that, there’s the stress of making forecasts for other people. I’m looking forward to the ease and enjoyment of just doing it just for me and not having to worry about how I’m going to communicate it to everyone else. ❆

This Wisdom piece was originally published in The Outliers Issue, out now.

Elevated Escapism: Bring home Backcountry five times annually with a subscription.

Go deeper with

The Outliers Issue

There’s a reason we keep coming back to the skintrack. Why we eagerly load skis into the car before the sun rises; why we diligently study avalanche danger and snow conditions; why we walk uphill for hours or fly across the world. It turns out there’s a lot we’re willing to do for a few (hopefully) good turns. Some are willing to do far more.

Meet The Outliers, the folks Issue 162 is dedicated to. Christina Lustenberger, Jim Morrison and Chantel Astorga: The athletes putting a first descent on one of the world’s most famous climbing walls. There’s Seth Beck, a splitboarder traversing the remnants of an ancient continent’s mountain range. And don’t forget Stratton Matteson: The man who spent five years forsaking gas-guzzling vehicles to make a statement about fighting climate change and kept logging epic lines in the Cascades anyways.

Of course, we’re still suckers for good ol’ fresh pow and a touch of history. Editor in Chief Betsy Manero dives into the origins of skiing, snow science and mountaineering in Japan’s northernmost prefecture and global powder capital, Hokkaido, and investigates the ramen and onsen-nurtured backcountry ski scene.

The rest? Well, you’ll just have to grab a copy to find out. And take your time, this issue will last through the corn, the mud and the sun.

The Backcountry Team

Related posts:

Wisdom: Sandy Ward