As someone new to backcountry ski touring, you may ski with more experienced friends and not be the one primarily responsible for planning your day out. But having an understanding of the planning process will give you insight into the decisions your ski partners are making and help you assess if you are comfortable with those or not.

Trip planning comes down to:

- Where to go

- What the snowpack conditions are likely to be

- The weather

- Strengths of the members of your group

- Making sure your group logistics are covered

Taking an avalanche course is the best way to familiarize yourself with safety and trip planning. Courses meeting American Avalanche Association or Avalanche Canada standards provide a solid overview of avalanche problems, companion rescue, trip planning and decision making in the field. Know Before You Go is also an excellent introductory resource.

Check the forecast

A regional avalanche center covers the terrain in most areas in North America in which backcountry skiers ski. Centers employ professional staff to issue avalanche forecasts throughout the winter. You should make a habit of finding and following yours.

How to interpret the forecast goes beyond our scope here, but pay particular attention to the section tagged “The Bottom Line” and remember that while the “Considerable” rating is the middle of the five-level danger scale, it still means that natural avalanches are possible and human triggered avalanches are likely.

Check the weather forecast as well. For example, if heavy snow (or God forbid, rain) is expected before or during your trip, that means the snowpack will be changing. You may need to reassess your plan.

Covering the bases

Your trip plan should be a good fit in terms of the fitness and skill level of your partners. Shooting for a 10-hour day or skiing tight trees may not be the best idea when planning a trip for a new group. It’s fine to think big, but wise to start small. You can always dial it up later in the season once you have experience with your teammates.

Pre-trip logistics include making sure everyone in your group has a transceiver, probe and shovel (and knows how to use them); that you have a suitable first aid kit, a map and compass (or more likely a phone with a navigation app); and some form of communication with the outside world. Make sure someone at home knows where you are going and what your trip plan is.

Terrain, terrain, terrain

The decision you make about where to ski has more impact on your safety than the stability or instability of the snowpack that overlies the terrain you chose.

Assessing a backcountry slope’s snowpack by digging a snow pit and performing a compression test is frankly beyond the expertise of a novice backcountry skier. Even skiers with years of experience know that assessing snow stability in avalanche terrain isn’t foolproof.

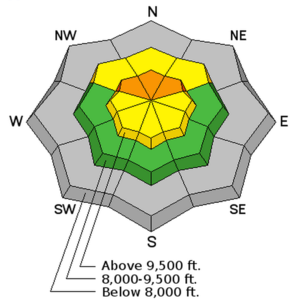

What does reduce your risk of avalanche involvement however is choosing to ski or ride lower angle slopes with no or limited overhead exposure. The Avalanche Terrain Exposure Scale (ATES) was developed in Canada and the concept is being adopted in the U.S. The scale ranks ski terrain as Simple, Challenging or Complex (ATES V2 adds Non-Avalanche and Extreme categories) based on terrain features regardless of snowpack conditions.

Whether you’re a novice or an experienced skier, you can have a lot of fun in relative safety by sticking to Simple terrain. That’s terrain that has exposure to low-angle or primarily forested slopes.

Low angle is defined as less than 30-degrees in steepness. A low-angle slope is much less likely to slide than a steeper slope, regardless of the condition of the snowpack. With good snow, low-angle slopes are pure fun to ski. For comparison, most blue and many black diamond runs at alpine ski resorts are at that pitch.

In Canada, many backcountry ski and mountaineering zones have been mapped and field-checked by experienced avalanche professionals. In the U.S., OnX Backcountry has begun to incorporate AI-generated ATES mapping into its product. Other map apps like CalTopo (and OnX) feature a slope angle layer that can give an indication of terrain angle.

It’s important to understand that these apps are not field checked like the Canadian mapping is and are approximating terrain characteristics. They are a good tool for getting a handle on unfamiliar terrain and what you can expect to encounter but should not be followed blindly. It’s important to remember that when using an app’s slope angle feature, remember to assess the approach as well as the zone you hope to ski.

Again, taking a snow safety course is highly recommended if you are serious about this sport. Assessing the avalanche forecast, weather forecast and terrain characteristics in advance is a prerequisite to keeping your head up and validating what you expected to find with what you are actually observing in the field.

One last piece of advice

It’s entirely possible that as someone new to the sport of backcountry skiing you don’t know anyone else that you can team up with to go ski touring. So, is it okay to go out alone?

No.

Sure, some people do it, but it’s not a sound idea, especially when you’re starting off. Skiing alone means you have immediately removed all chance of a companion rescue if you get buried or will have to entirely fend for yourself in the cold if you get hurt.

There have been several accidents in the last few years in which highly experienced skiers couldn’t find a partner for the day, elected to head out anyway and were unfortunately caught and fully buried in a slide that a partner could have dug them out of, but that they couldn’t get out of themselves. No one expects that to happen, but it can.

Skiing in the backcountry alone is like driving your car without a seatbelt or riding your bike without a helmet. Everything is cool until it isn’t. Look for an outdoor club where you might meet a partner, or better yet, take a snow safety course at which you might meet someone to have fun with.

Brett St. Clair, with Craig Evanoff, is the author of Tips for Beginning Backcountry Skiers. Brett can be reached for questions or comments at brett@wskyline.com. If you’re an experienced backcountry skier but know someone who’s new to the sport and might find these tips useful, why not share this with them?

Related posts: