[This article is part of our week of climate change coverage, through which we hope to build awareness, dialogue and action around the topic as our alpine communities become increasingly impacted.]

Reviewed by Sarah Boon

As an environmental scientist and mountain hydrologist, I tend to consume a lot of literature on the subject of climate change. Some recent reads I’ve enjoyed in this genre include David Wallace-Wells’s The Uninhabitable Earth, Mark Serreze’s Brave New Arctic, and Lauren Oakes’s In Search of the Canary Tree. All three books cover climate change but focus on different ecosystems: Wallace-Wells talks about climate change and humanity’s role therein, Serreze talks about how scientists finally decided global warming was affecting the Arctic, and Oakes learns about how local Alaskan people feel about the climate-change-induced decline of the yellow-cedar tree.

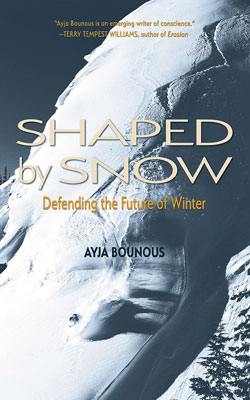

And so I was drawn to Shaped by Snow, by author Ayja Bounous, who has followed the most important rule of science communication: connect with the reader through what they care about. In her book, she shares her own outdoor experiences while describing the very real threats to mountain ecosystems from climate change.

Bounous’s book is important because it doesn’t just tell stories of mountain adventures—she also includes information about what’s happening in the mountains as a result of climate change. She discusses how landscapes are morphing, from glacier retreat to earlier alpine flower blooms and late to no snowfall in typically snowy areas, to paint the picture of how mountain regions are bearing the full brunt of climate change.

Bounous is passionate about mountains, and it shows. She comes from a family with deep mountain roots: her grandparents were instrumental in developing downhill ski resorts in Utah and her parents were worldwide downhill ski guides until they re-settled in Utah where her father became a downhill racing instructor. Through it all, Bounous and her sister have been part of a dedicated outdoor family that loves nothing more than a day in the mountains.

But those mountains are changing, and Bounous shares the stories of climate evolution that are taking place. As a mountain hydrologist, these changes are all sadly familiar to me. I see less snow and more rain and have witnessed the shrinking snowy season. Climate warming in mountain regions means that specific ecosystems are moving uphill, where it remains colder, longer, as plants and small mammals try to maintain the climate they’re used to. At a certain point, however, there’s no place to go.

Bounous discusses these changing landscapes as a way to illustrate how climate change dynamically effects mountain regions and elaborates on how changes in the timing of winter snow fall and spring snow melt are significant for ecosystems, as snow is needed to insulate the ground to allow small mouse-like mammals like alpine pikas to exist under the snowpack throughout the winter. In spring, snowmelt determines when alpine meadows bloom, which brings in pollinators from near and far. If snowfall is delayed, there isn’t enough insulation for small mammals to survive freezing temperatures. Conversely, if snow melts too early, pollinators arrive after a flower bloom is over, leaving them starving.

Amid these technical descriptions of ecology and climate, Bounous includes compelling personal stories that balance her academic-oriented passages. When Buonous describes how she and her mother get caught in a mountain thunderstorm, complete with knee-deep hail, the cold unpredictability is tangible for the reader. The uncertainty Buonos and her mother have about whether they should hunker down or race to safety in the face of the storm is a relatable fear that becomes palpable on the page.

When it’s time to discuss scientific concepts, however, Bounous’s tone becomes more detailed and technical, sometimes in a matter that inhibits her storytelling style. She describes matter flowing in the stem of a tree, talking about xylem, phloem, and chloroplasts in technical terms. “When sunlight is absorbed into chloroplasts—cell structures embedded in leaves—the energy from that light is used to deconstruct the H2O and CO2 molecules,” Buonos elaborates.

But when she naturally scatters scientific facts throughout her personal anecdotes, her tone becomes more free flowing. “As climate change impacts how vegetation grows in the Wasatch, warming alpine ecosystems, species that historical grow in lower, warmer elevations are moving higher in elevation, outcompeting current vegetation. Trees and shrubs are encroaching on alpine meadows,” she pens about how mountain goat habitat is moving upward in elevation as lower alpine regions warm.

And as a member of a downhill ski family, Buonos doesn’t back down from calling out the alpine ski industry for their environmental impacts. From carbon emissions generated by car commuters and the impact of cross-country flights on skiing’s footprint, she presents the dirtier side of skiing in Shaped by Snow. She also notes that the average ski season in North America could be reduced by 32 percent by 2050, and by 90 percent by 2100.

And through the lens of climate change, the reader follows her through the development of a new relationship, the loss of her grandparents, her inferiority complex when skiing with her father, and the decision of whether or not to have kids.

As an environmental scientist, I was drawn to a book about climate change, but I harbour reservations about the technical jargon Buonos uses throughout the book. I believe that in order for a large readership to absorb scientific material, data must be presented in a digestible and approachable way. I understand the processes Bounous is writing about, but I’m not convinced that the reader really needs to know the details of snow crystal formation or of water flow through trees. Her saving grace: compelling storytelling that captures the reader imagination enough to bring them through the quagmire of scientific detail.

Related posts: