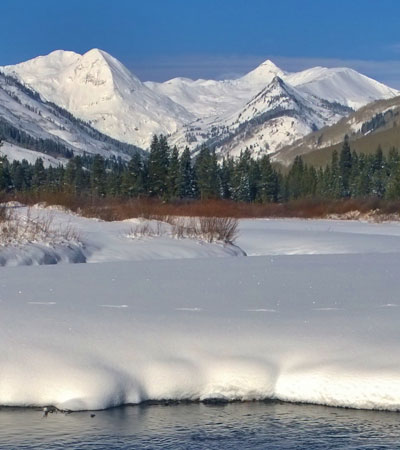

Nordic skiers slide along groomed trails with Paradise Divide looming in the background. [Photo] Courtesy Silent Tracks

When Frank Konsella moved to Crested Butte a quarter-century ago and began hunting for ski partners, he recalls being on the receiving end of a one-two punch: “Question number one: Do you have any avy training? Question number two: Do you have a sled?” he recalls.

Snowmobiles, he argues, are a staple of the touring scene in and around the remote Colorado mountain hamlet because of distance and safety. First, few of the unpaved forest roads that lead into the heart of the mountains are maintained in winter, which can mean anywhere from five to 12 miles of mostly flat approaches to reach skiable terrain—long slogs that aren’t quite flat enough to skate and that can add hours to a skinning tour. Second, Konsella says, “We get a deeper, safer snowpack farther away from town.”

Konsella arrived in town just in time for the 1994-’95 season, the last winter of permitted snowmobile travel in Gothic Basin north of town, one of the six main drainages surrounding Crested Butte that serve as winter recreation hubs. The next winter, Gothic Basin went dark to snowmobilers as part of the so-called “Gang of 9 Decision”, when nine people representing different recreation interests helped shape the local winter travel management plan to delineate terrain primarily for snowmobiling and other terrain for cross-country skiing in the upper valleys.

The Slate River Valley abuts the base of Paradise Divide [Photo] Courtesy Silent Tracks

That decision set aside another drainage, Kebler Pass to the west, as the main snowmobile corridor and left the area’s other zones open to both types of winter access. One in particular to the southeast of town, the Slate River, was designated as having an “emphasis on general, non-commercial use” in the official plan.

But over the ensuing 25 years, traffic along the Slate has boomed alongside Crested Butte’s own population and the town’s reputation as a winter sports mecca. Today, a typical winter scene on snow-covered Slate River Road might see snowmobiles laden with skis, commercial dog sled operations with tourists in tow, cross-country skiers from the nearby Nordic center, fat bikers with hands stuffed in oversized gloves and even townspeople walking dogs on the firmly packed snow.

Unlike certain pathways into the mountains where the terrain or management, like trail grooming, seems to favor one mode of travel over another, “It’s the only drainage that everybody really just loves,” says Brittany Konsella, Frank’s wife.

The ski mountaineering couple, who have both skied all of Colorado’s 14ers, are co-authors of Backcountry Ski & Snowboard Routes: Colorado and co-founders of Share the Slate, an advocacy group hoping to maintain snowmobile access in the Slate Valley.

“The guidebook gave us an excuse to travel to other parts of the state where we weren’t able to backcountry ski during our 14er project,” Brittany says. “We believe in promoting an outdoor lifestyle because being outdoors helps people’s mental health and well-being and the very connection with the outdoors helps foster a need for recreational preservation of the lands we love.”

Backcountry skiers skin through a quiet snowstorm in the Slate River Valley. [Photo] Courtesy Silent Tracks

The Slate drainage accesses 12,000-13,000-foot peaks up at Paradise Divide near the river’s headwaters, and runs nearly a mile wide at its mouth, located at roughly 9,000 feet in elevation. Snowmobilers park their rigs at the Slate River winter trailhead, just three miles from town where the mouth of the drainage incorporates part of the Crested Butte Nordic Center.

“You can leave from your back door in town and take groomed Nordic ski trails, then proceed from town directly up the Slate River drainage as high as you are comfortable going,” says Bill Oliver, a retired engineer who settled in Crested Butte nearly a decade ago. On metal-edged skis, he is a regular traveler up the Slate in winter, though he says he sticks to the lower reaches of the drainage because he doesn’t have avalanche training. “Plus it’s a pretty arduous climb,” the 64-year-old says with a laugh.

Oliver sits on the board of directors of Silent Tracks, an advocacy group that formed in 2015 to promote the interests of non-motorized backcountry travelers, or what the group likes to call “quiet users.”

Both Silent Tracks and Share the Slate formed to give their constituencies a voice as the local National Forest district prepares to revise the 1995 Gang of 9 Decision. The district will be drafting a new winter travel management plan for the mountains around Crested Butte hopefully by 2020 in response to the U.S. National Forest Service’s 2015 Over Snow Vehicle Rule, which requires all national forests that receive sufficient snowfall to write such plans and, in the case of places like Crested Butte, to dust off the old ones and update them to today’s winter travel conditions where backcountry users of all stripes are more prevalent and snowmobiles can reach further and higher than ever before.

Silent Tracks sprang up first out of concerns that winter solitude was becoming extinct. “If I’m trying to ski up the Slate drainage on the one winter trail and I’m being passed by snowmobiles every 5 to 15 minutes, sometimes in tour groups, it really detracts from the skiing experience,” Oliver says. “What’s going to happen in the years to come, and is there going to be any place to find quiet?”

He points to survey data collected by students in Western Colorado University’s Master in Environmental Management Program, which tallied different types of visitors at the Slate River Trailhead during the 2016-’17 winter. Collectively, two-thirds were non-motorized users.

But the name “Silent Tracks” raised concerns that the group wished to ban snowmobiles entirely in partnership with the Crested Butte Nordic Center, which was potentially eyeing expansion of its groomed terrain in the Slate region. The mere suggestion of such a preference sparked a small-town row in 2015, with one prominent local business owner calling out both entities in an open letter for encouraging “polarization.”

Since then, cooler heads have prevailed. Leadership has changed at the Nordic Center and Silent Tracks insists they are not looking to outright ban any form of winter travel. “The root cause is not snowmobilers or non-snowmobilers, it’s just the number of people inundating not only our community, but mountain communities in the west,” Oliver says.

The Konsellas concur, but don’t see a solution in keeping out so-called “hybrid skiers” who use snowmobiles for those long road approaches. “If the Slate were to be taken away from what we access, we would have more people skiing on top of each other in the backcountry,” Brittany says, noting that the drainage accounts for up to half of the region’s backcountry skiing traffic.

Ultimately, the matter that prompted the kerfuffle—the Over Snow Vehicle Rule—has turned into a hurry-up-and-wait situation. The Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison (GMUG) National Forests, which include the area around Crested Butte, have “no specific timeline” to begin the winter travel management planning process, according to the combined forest district’s public affairs officer, Kimberlee Phillips. Winter travel planning will not begin until the unit’s ongoing forest plan revision is completed.

But in the wake of the 2015 dust-up, locals are learning how to manage competing desires for the backcountry with increasing recognition that everyone is going to have to learn how to get along. Etiquette posters sponsored by Silent Tracks and prepared with input from Share the Slate have popped up around town encouraging skiers to move aside for passing snowmobiles and entreat sled drivers to slow down and wave when passing. Share the Slate even published a dog poop pick-up guide.

The most promising sign that conflict may yield to cooperation came in late 2018 with the help of Western Colorado University, which hosted a four-part winter travel management seminar series. The seminars covered management models from elsewhere in Colorado like Wolf Creek and Vail Pass, a national overview from Winter Wildlands Alliance, academic research bringing a data-driven approach to a topic often fueled by emotion, and a chance for both Silent Tracks and Share the Slate to have a word.

“What excites me about the possibility of winter travel management planning in the GMUG is that this could be a tremendous laboratory for trying and evaluating innovative approaches,” says Western Colorado professor Melanie Armstrong, executive director of the Center for Public Lands, who spoke at the seminar series and whose students have researched issues like the Slate. “We need new conversations about land management that can acknowledge a dynamic landscape—in terms of population growth, visitor use, and climate change—and still forge ahead in planning and doing.”

While the Forest Service is largely mum about what the future planning process holds, the seminar series has nurtured optimism that a solution amenable to all can be found.

“The best outcome will be a broadly supported and thus implementable plan both in the Slate River valley and across the planning area. Our success will rest on the district’s ability to strike a durable balance between the competing needs of the resource and the people who rely on it for a variety of benefits,” Phillips says. “It’s a tall order but based on the Gunnison Country’s tendency towards innovation, I’m very hopeful we can deliver a process and outcome that generates [an] elusive balance.”

The Konsellas, who feel like they have the most to lose if the status quo changes, are guardedly positive. “User groups are still holding our ground where we are,” Brittany says. “But the one thing I feel lucky about is living in Gunnison County. A lot of user groups that would be at others’ throats tend to work together here. Bringing us together with the lecture series was a step toward that.”

Great solutions-oriented story here! Disparate user groups can co-exist!

The primary complaints regarding snowmobiles are typically noise and emissions. I hope that sled vendors in the Crested Butte area are aware of the new electric snowmobiles and will start promoting them. They are relatively expensive now ($15,000+) but prices will drop as demand increases and battery technology continues to improve. https://taigamotors.ca/snowmobiles/

I wonder if the parties involved would consider an even-day, odd-day rotation for when motorized recreation/transportation is allowed and when it isn’t.