Jonathan Charlet leads the charge, while brother Jean-Baptiste follows, up the ever-steepening Washburn Way on the Aguille Verte far above Chamonix, France’s Argentière Glacier. [Photo] Ryan Irvin

There’s enough space in the tram for a cart full of baguettes. This is France, after all, and the warm, fresh bread is as indispensible to a ski patroller’s daily checklist as his gurney, spool of rope or bulky trauma bag.

It’s just after 8 a.m., and they’re loading the first bin of the day, ascending toward the summit of Grand Montets in the Chamonix Valley, where the morning cloud cover is leaking streaks of sunlight onto the cold, blue peaks holding up the sky. If there’s room for bread, then surely the patrollers have no objection to squeezing in Jean-Baptiste “Babs” Charlet and his chatty, animated brother, Jonathan “Douds” Charlet, along with fellow steep-skiing phenom Vivian Bruchez and a wide-eyed journalist.

As the tram rises and espresso breath fogs the plexiglass, a short, white-haired patroller with weathered lips and squinty wrinkles wrapping his glacier glasses pipes up to ask the gentlemen what they plan to ski.

“We’re going to look at the ribbon of snow across the north face of the Petit Dru,” Bruchez says in French. The patrollers react with raised eyebrows, understated disbelief and a tinge of admiration. They know better than to caution these lifelong locals carrying a centuries-old legacy of reconceiving what’s possible in the mountains. They also know that legends perish in this valley on a more than regular basis.

Above the piste, a fresh dusting of powder sits on cold, crunchy spring snow. Douds (pronounced “Dudes”) hikes up his baggy pant legs and straps into a splitboard before howling down through Les Autrichiens Couloir in the Pas de Chevre basin, minding a windslab and letting out a Roger Rabbit cartoon laugh while barreling into the abyss. Babs follows with a surfy frontside slash high on the right wall of the chute before they glide across the glacier to the foot of their objective. Bruchez follows on skis with more cautious turns.

“My father climbed this,” Babs says while gazing up at the jagged spire of the 3,733-meter Petit Dru. In fact, his distant relative, Jean-Esteril Charlet, claimed the very first ascent in 1879 with little more than a rope and crampons lashed to leather boots.

The Charlets don’t have to dig deep into the closet to find traditional French mountaineering garb, much of it adorned with the prestigious seal of the Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix. Left to right: Jean-Franck, Jean-Baptiste and Jonathan. [Photo] Ryan Irvin

The trio ascends a sluff-peppered apron over a bergschrund and up the approach couloir that’s been heavily deposited with snow from the vertical walls rising thousands of feet on either side. Halfway up, below a hanging, glaciated icefall, they dogleg left and climb another 300 feet to a horizontal bench of snow that looks to be painted sideways across the rock like a crooked mustache laughing on the face of Les Drus.

Bruchez belays Douds through the mixed traverse, and they steadily ascend 550 meters in a three-hour bootpack with an ice axe in each hand. Just before 2 p.m., Douds drops into the upper section of the couloir, floating through a dozen overhead powder turns before pulling into the “safe zone” on the edge of an 800-foot vertical drop-off. His sluff rains down the face in a white curtain before Bruchez and Babs follow to the second skiable section—the horizontal sliver that drops them back into the main couloir and out from the 4.5-hour mission.

Babs demonstrates classic Chamonix snowboarding style: jump turns with an ice tool in each hand. [Photo] Ryan Irvin

“I felt like I was skiing on clouds with the massive exposure,” Bruchez says at the bottom as we all celebrate the first descent of “La ceinture des Drus” in a patch of sun with Comté cheese and apple sausage. “It was a strange and amazing feeling to ride in the middle of a vertical wall that I’ve climbed before,” Douds says while rolling a smoke. It’s the day after his first daughter Luna’s sixth birthday, and he’s especially happy to be alive.

After rappelling down to the Valle Blanche glacier and downloading the Montenvers train, the men are greeted back in Chamonix with a round of panaché beers on a sunny terrace by Douds and Babs’s father, Jean-Franck Charlet, who’d been watching them climb the line with binoculars from the valley floor. He might as well be saying, “So, what did you do in school today, boys? Ah, yes, I remember when I did that years and years ago.”

He kisses and congratulates them with a leathery smile until they show him Douds’s iPhone photos of the thin shelf of snow they rode, perched above certain death. Jean-Franck grimaces with each swipe through the camera roll. “Too extreme for me,” he says. “I was up there for rock climbing, not to ski this.”

And so goes the Charlet family paradox—five generations of alpinists pioneering routes in the birthplace of mountaineering while the latest generation retraces these lines with a more modern, gravitational approach: snowboarding. Just three days before, the brothers nabbed a second snowboard descent of the Washburn Line, which Bradford Washburn opened up in 1929 while being guided by their grandfather, George Charlet. They’re following in the family footsteps, just with snowboards on their feet.

Back on the balcony of Jean-Franck’s house up valley in Montroc, a high-powered spotting scope sits on a tripod trained on the rock towers, snow-covered ridges and steep couloirs for which Chamonix is known. But the Charlets don’t need it to point out many of the lines that their forefathers first climbed or skied.

Isabella Charlet-Straton made the first winter ascent of Mont Blanc in a dress with her future husband, Jean Charlet, in January 1876. The brothers’ great, great uncle, Armand Charlet, did the first winter traverse of Les Drus in 1938 after many first ascents on the Aiguille Verte. During World War II, Armand used his mountaineering skills to assist people crossing the frontier in defiance of the Germans. Douds is cavalier in pointing out the face on Le Tour where their grandfather, Jean-Paul Charlet, died in an avalanche at 59 while guiding clients in 1993. Jean-Franck himself has an icefall named after him on the north side of the Col de la Verte.

“What could be more symbolic,” Bruchez captioned on Instagram, “than to pay tribute to the pioneers of mountaineering and skiing by sliding in their footsteps.”

Bruchez is not alone in his respect for this tradition. Nathan Wallace is an American skier who’s spent two immersive decades in Chamonix, becoming an honorary local and watching Babs and Douds grow up. “Much like if you were a musician or a poet back in time, mountain climbing was an extension of the ultra wealthy class,” he explains. “Barons or dukes would want to climb something, and often one of the Charlets would be involved. Look at the guidebooks, and they’re the most prolific family in Chamonix.”

Vivian Bruchez and the Charlet brothers work their way across a bergschrund on the Petit Dru en route to “La ceinture des Drus.” [Photo] Ryan Irvin

The earliest mountain explorers of this region were 18th century farmers herding their cows into the valleys with wool socks on their hooves to cross the abrasive glacier snow. That’s when they discovered iridescent crystals buried in tight caves called “ovens” scattered across mountain faces. Chamonix’s first alpinists were farmers turned crystal diggers, climbing or rappelling thousands of feet on sheer rock faces with primitive equipment to harvest these valuable treasures. When tourists first arrived in the valley looking to explore the mountains, the crystal diggers became their escorts, but even today, some guides still scour the mountains for crystals, hunting the thrill of discovery and extra income. Jean-Franck’s living room is littered with crystals giant and small, sparkling white and intensely black, translucent pink and deep red, in glass display cases, under LED lights and perched above the kitchen sink. Babs carries pea-sized pink and white quartz rocks in the pocket of his jeans, and Douds has been known to detour a 55-degree bootpack to a cliff wall to check for shiny rocks. Crystal digging goes hand in hand with the alpinism that runs thick through their Charlet blood.

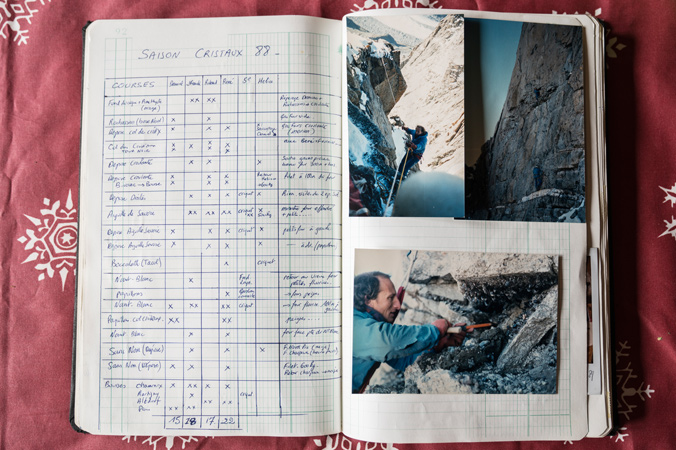

Jean-Franck Charlet’s journal with notes and photos on the art of quartz harvesting, the Charlet family’s other passion. [Photo] Ryan Irvin

Douds shows off one of his most prize quartz pieces, harvested from within a stone’s throw of his home. [Photo] Ryan Irvin

But when Babs (40) and Douds (34) were kids growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, all they wanted to do was skateboard. Any time they were in Paris or Lyon or even smaller cities, Babs would be skating, and when they weren’t, he was dreaming of pavement. In 1991, Babs was 12 and snowboarding was transitioning from a slalom racing sport to freestyle and halfpipe, so Jean-Franck put him on a board. “He very quickly started winning,” Jean-Franck says while wearing his old, woolen guide jacket and hat. “He was the only one doing 720s and, by 16, he was junior world champion.”

At the time when everyone was expecting Babs to rock climb and become a mountain guide, he was hitting rails and transitions, going on to compete in the 1998 Olympic halfpipe event in Nagano, Japan. He now runs a snowboard school in Chamonix.

Babs is still known throughout the Alps for his smooth riding style, while hyperactive Douds was always the wild, breakdancing little brother in tow. His baffling flexibility makes him catlike in the air, but a freestyle obsession brought many injuries to his wrists, ankles and knees, and he never became a world champion or Olympian. He did, however, capitalize on the home-field advantage of a 2013 Freeride World Tour stop in Chamonix, where he took first place on a wildcard spot, eventually winning the overall tour two years later. His confidence landing big airs on 60-degree slopes certainly helped him earn these titles. But you need both technical skills and some nerve to throw a 360 on the Aiguille du Midi’s north face, especially on the high-consequence Col du Plan that enters above a massive serac and drops hundreds of feet beside a tight couloir requiring several rappels to exit.

“I know exactly where [an] avalanche will be and how to cut a slope,” Douds says. “The only way to ride a couloir fast is to be in front of your sluff.”

“Speed is also your friend,” Babs adds.

Douds earns style points on the Pas de Chevre on his way to the Petit Dru. [Photo] Ryan Irvin

In his 20s, Douds got more into rock climbing and alpinism while working on his mountain-guide certification before ascending the ranks of the prestigious Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix, of which Armand’s son, Jean-Claude Charlet, was president from 1990 to 1994. “I’m very proud to be part of this with my father and family,” Douds says with a humble head bow.

“To me, he’s the best steep snowboarder in the world, hands down,” says Wallace, chuckling over the irony that Douds rides old, off-brand gear and has few sponsors. “Babs has the best style in the world, but Douds is just like having a combination of Jeremy Jones, Xavier de Le Rue, some badass alpinist and Terje Håkonsen.”

On another crisp April morning, Douds is bopping and singing a French reggae song during the 9,186-foot cable car ascent of the Aiguille du Midi. The day before, he and extreme skier Christophe “Tof” Henry made a gutsy second snowboard descent and first ski descent of a vicious line on the north face of the Triolet, which included a rappel off the end of a hanging serac in rapidly rising temperatures.

“I know the gear more than the serac. It can hold an elephant,” Douds says when I ask him why he chose to leave gear behind, rather than rappelling off a V-thread. “I leave the [ice] screw in because we are under a big serac and I have two kids.”

Today they’re planning to ski the Pain de Sucre, a seldom-repeated line with a vertical, mixed bootpack approach and a protected north-facing powder field above more massive exposure, gaping bergschrunds and a sketchy series of traverses and rappels to the Glacier d’Envers de Blaitiere. They invite me to tag along, and the south-facing approach up the Glacier d’Envers du Plan is hot and sweaty as we cook on the snow’s ultraviolet reflection. Without explanation, Douds looks as though he’s raided the closet of his progenitors, wearing an old, wool button-up, wool blazer-type jacket, wool bucket hat and an elastic-strapped bow tie. He’s also carrying a long, straight, wooden relic of an ice axe that must weigh eight pounds with rust covering the dull pick.

Douds skins toward an unskied ribbon of snow glued to the side of Petit Dru. [Photo] Ryan Irvin

His knack for tradition doesn’t stop at the wardrobe. After both Douds and Tof paint the face with smooth, arcing turns, the exit traverse gets tricky and we run out of anchor points for one of the rappels. Douds digs out a platform in the snow with a shallow lip and carefully deadman anchors his ancient ice axe into the snow with one rope strand running below, the other to the axe’s spike. We use the line to cross through the choke, then Douds lassos the rope’s slack in a sort of fly-fishing cast that somehow flips the wooden axe free, pulling it in with a high-pitched “Ah-ha!”

He smiles at the ease of this ultra-classic move, then holsters the axe like a sidearm and takes off riding switch down the slushy apron, popping spins and tweaked-out grabs before pulling up to a towering rock wall and gazing at the scarred granite face. “Crystals!” he shrieks, pointing up to a small cave of shiny quartz hundreds of feet above. “I come back here later and have a look.”

Related posts:

Salomon and Atomic’s new tech/alpine Shift MNC 13 aims to do it all with enhanced safety

Fearlessly Female: Jan Reynolds on life up high and advice for aspiring women ski mountaineers