Andrew and I arrived at the top of Safety First, a slackcountry-sidestep beyond Vancouver Island’s Mount Washington Alpine Resort, excited about the six inches of fresh. But we were also a bit nervous about the potential for wind slab on the first convex roll.

We discussed how to manage the first few turns while we waited for our snowboarding buddy Phil to catch up. He’d been lagging since we ducked the resort boundary line, and while we’d waited for him at all the key spots along the traverse, we left him strapping into his board at the highpoint. As we set up for a ski cut, Phil appeared out of the forest, bombed right by us and dropped over the roll. Mouths open in shock, we watched him rip out a small avalanche and go for a ride through the timber. Even more surprising, he emerged unscathed and unapologetic.

This happened a decade ago. Right up until last winter I always looked at the incident as entirely Phil’s fault. But one class into Ken Wylie’s course, Mindful Applications for Adventure Risk Management, I started to see things differently.

In 2003 Wylie was guiding at a B.C. lodge when a slide buried him and most of his group. Seven people died, including legendary snowboarder Craig Kelly. Wylie wrote the book Buried about his journey to understand and address his behaviors and decisions that led to the accident. Eight lessons and 18 years of reflection are at the heart of his mountain mindfulness course.

“We’re playing with fire if we go into an environment that can kill us and we don’t prepare mentally for it,” Wylie says. “We need to learn to use adventure and reflection to make better decisions about risk and develop as human beings.”

Wylie’s course starts where most avalanche courses end when it comes to soft skills—human factors contribute to almost every avalanche incident—and then dives into the tools and tactics to identify and manage how and why we make the decisions we do. Not just providing skills for the skintrack, the course offers information for making any important decision or building any relationship. It’s the kind of stuff that prevents accidents without you even realizing it.

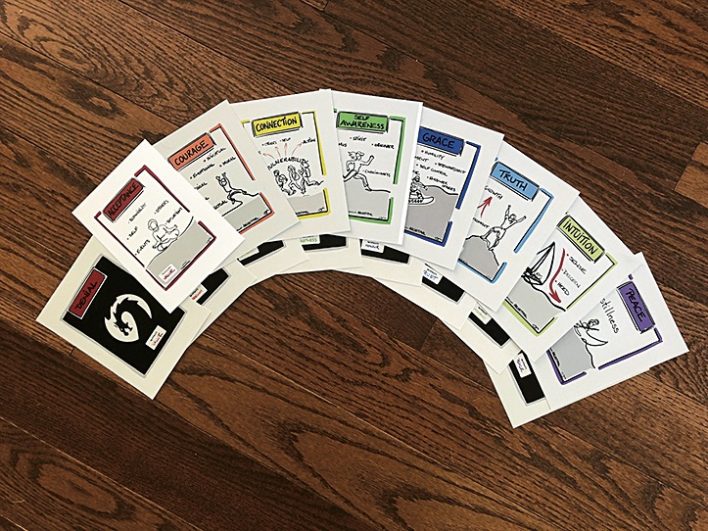

The course focuses on eight cards Wylie designed specifically for the purpose. Each is labeled, front and back, with a pair of concepts that relate to decision-making (see sidebar on next page). The front is the light side, with drawings and words related to it. Wylie gleaned these nuggets from reflecting on his own mountain experiences and from universal values that transcend cultures, he says. The back is the shadowed opposite, our negative human factors, or dragons—traits that lead us and those around us to make poor decisions.

“Nature always tries to teach us there are two sides to everything,” Wylie explains, pointing out summer and winter, yin and yang, frontside and backside. “It’s best that we make friends with both the shadow side and light side, so we can learn and engage.”

Wylie developed the course as an in-person retreat. That’s how he ran it a few times before the pandemic forced him online. Over Zoom last February and March I joined seven other students from across western Canada for two hours every Wednesday night. Each week Wylie would introduce one or two of the cards, using mountain anecdotes and psychological insights to give them context. He regularly quoted psychologists like Carl Jung and Brene Brown, and modern thinkers on performance and decision-making like Daniel Kahneman, the author of Thinking, Fast and Slow, and Steven Kotler, the author of The Rise of Superman. We discussed ideas as a group, injected our own experiences and worked on exercises that pushed us to think about our own decision-making dragons—and how to tame them.

By the second session I was looking at Phil’s behavior on Safety First differently. Andrew and I hadn’t accepted that Phil was going to move slower than us. We didn’t empower Phil to have the courage to tell us how he felt. By repeatedly leaving him in our dust, we eroded our group connection. I wasn’t self-aware enough to realize my ego was pushing me to keep up with Andrew. Phil was probably frustrated and ego-bruised, and that’s why he plunged right in. My own actions played a significant role in his behavior and ultimately led to chaos.

“The more you work with the cards, the more you see where your choices are going,” says Wylie.

One of the big lessons is that everything is a choice—even when we’re silent or think we’re not making one. Wylie compares it to not voting in an election. “When you’re not engaging in decision-making you are still making a choice,” he says. “Accept it or deny it, you’re still responsible for the outcome.”

As the course progressed I thought of other accidents, near misses and mini-epics with new eyes. And, after it was done, I went into the backcountry looking for risks beyond the slopes, including my own mental state and that of the people I was with.

At critical moments I’d think beyond how I came to a decision. I’d scroll through the cards in my mind, questioning if I was accepting today’s conditions or denying the warning signs. Was I creating opportunities for my friend to share his thoughts? Was I agreeing with the assessment because I avoid conflict? And, trickiest of all, was that feeling in my gut intuition or fear?

I also felt more present. Instead of overthinking, like it might sound, I was actually more relaxed and observant, consciously seeking information about snow conditions and weather, my own state of mind and body, and what was going on with my companions.

Wylie also provided a vocabulary. For me, giving feelings or actions a specific name made decisions more solid and harder to justify my way out of. “I’m accepting that the conditions are touchy, so I’m skiing inbounds” felt more secure than “the avalanche danger is high, so I’m skiing inbounds.”

For Wylie, the impact of the course could reach even further. “Going out backcountry skiing or rock climbing is such a selfish endeavor,” he says. “But I think we can shape and reflect on adventure so that your friends and family are excited for us to go to the mountains because they know you’ll come back a better person.”

I’ve never heard a better excuse to go skiing.

Sleight of Mind

How to use mindfulness cards:

Each of the eight cards at the heart of Ken Wylie’s Mindfulness Applications for Risk Management course build on each other. Acceptance leads to courage, and in turn connection and so on. They also spiral the other way: Denial leads to fainthearted decisions and isolation. Look around and you will see them at play in everything from the office to family life—and definitely when making decisions.

Facilitated discussions deepen the connection and understanding about each card. So does reflecting and discussing them. The more time you spend with them, the more helpful they’ll be. —RS

ACCEPTANCE/DENIAL: When we deny the reality of a situation or feeling, we’re not seeing everything that’s going on, which means we’re missing important details.

KEY QUESTION: How honest are you being about what is actually happening?

COURAGE/FAINTHEARTED: We tend to misunderstand courage. It’s not about being the lion. It’s about facing a scary challenge, experiencing it, managing it and moving forward.

KEY QUESTION: Are you making this choice because you’re afraid or despite the challenges it creates?

CONNECTION/ISOLATION: Connecting with yourself, your companions and the place requires vulnerability, respect and communication.

KEY QUESTION: Are you engaging in all three to solve the problem?

SELF-AWARENESS/INSIGNIFICANCE: Defining ourselves by what we do for fun or work leaves us vulnerable to losing our identity and our feeling of worth, skewing our decision-making.

KEY QUESTION: Who are you when you strip away your activities?

INTUITION/INTELLECT: Intuition is not fear or previous experience that is now automatic. It’s learning to hear, trust and act on our inner voice and collective consciousness.

KEY QUESTION: How does this decision make you feel?

TRUTH/DECEPTION: There is no one truth: witness political polarization or any spirited debate. Considering all information, regardless of the source, helps us see this dark side more clearly.

KEY QUESTION: Are your motivations impacting your “truth?”

GRACE/HUBRIS: This is about intention and self-control: nurturing hubris, gratitude, empowerment and movement.

KEY QUESTION: Could pride be playing a role in what you are doing?

PEACE/CHAOS: The sum of all the other cards. Operating entirely on the light side leads to the “flow state,” a complete absorption in what you’re doing. On the dark side is chaos.

KEY QUESTION: If you don’t feel peaceful, which link in the chain needs work?

Learn more about the Mindfulness Applications for Risk Management course and Ken Wylie at archetypal.ca.

This article first appeared in Issue 141, The Avalanche Issue. To pick up a copy, go to backcountrymagazine.com/141, and to see stories earlier when they are published in print, subscribe.

I don’t want to make too much light of what is definitely a serious subject, but I was immediately struck how one of this Canadian’s comments took me immediately to the lyric written by another Canadian: “If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice” by Rush.

Awesome comment!!!

https://www.archetypal.ca/human-journey-card-deck-1

Ken’s course and materials are second to none and really are a “must do” for anyone who participates in risk sports recreationally or professionally. Ken has developed them and tailored them over decades for all of us. They are highly usable and practical, and even become a kind of vocabulary amongst risk taking practitioners. Take his course. The mindfulness you will walk away with will aid you in assessing risk in all of your risky endeavors. I found I even relate back to Ken’s paradigm when I make difficult business and engineering decisions. Thank you Ken for enriching my risk management skills and awareness in sports, business and engineering. Very valuable for anyone assessing and taking risks.