In 2003, Brian Irwin wrote an article for Couloir about Phillips Brook Backcountry Recreation Area. This spring, the founder of the New Hampshire backcountry yurt system passed away. Twenty-one years since writing the initial article, Irwin reflects on Altenburg’s impact on backcountry skiing on the East Coast.

by Brian Irwin

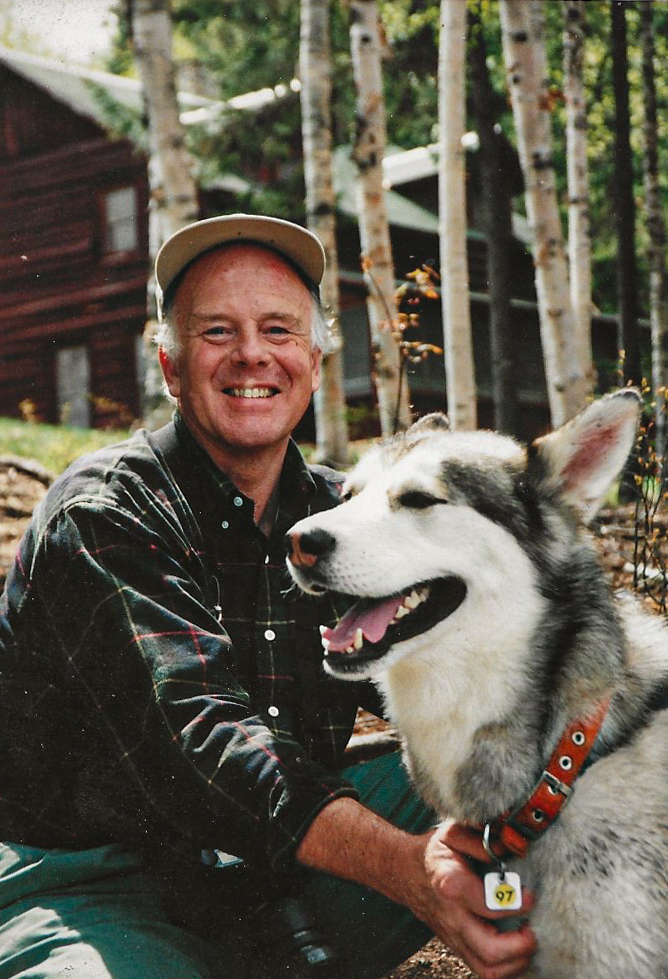

“So you’re a flatlander?” asked Bill Altenburg, upon hearing my plans to visit the Phillips Brook Backcountry Recreation Area, where Altenburg had erected a system of yurts among already-thinned, leased International Paper Company land in the sparsely populated region of Northern New Hampshire. Altenburg was referring to my mid-Atlantic Maryland roots, shed gladly when I moved north in search of solitude, powder and solid people like Altenburg. He graced my life for 22 years before taking the big skin track in the sky on May 11, 2024.

I immediately liked him. Altenburg was a driven, direct man, polite and kind, with frosty whiskers, wool pants, suspenders and the requisite three-pins. And no, he didn’t use a spring heel cable. He was too pure for such an aid.

He agreed to host me at the now-shuttered Phillips Brook site to write an article for Couloir which has since merged with Backcountry Magazine. It was my first ever article. Altenburg didn’t believe in territorialism, he believed that backcountry skiers all lived by the same code; that when we’re all towing cold smoke it doesn’t matter if it’s in a tree burn or a New Hampshire clearing, we’re all part of the same community. That’s how Altenburg saw the world.

Altenburg was a trailblazer in a way that most backcountry enthusiasts don’t recognize. Before him, backcountry eastern link-ups were restricted to the Appalachian Mountain Club’s huts, almost none of which are open in winter, and are laid out for hikers, not skiers. There was little interest in multi-day ski trips in New England before Altenburg. AT gear was primitive, tele gear was evolving. It was a different time, one where you had to really search for resources, gear and worthy destinations. That’s where Altenburg made a difference.

He stoked the flames of enthusiasm for backcountry skiing in the east when it was a nascent pastime enjoyed by only a few. He practiced responsible glading. He proved that the east could indeed offer a hut-to-hut experience, previously absent before his time. Organizations like the Granite Backcountry Alliance may not even exist without his example. Altenburg changed the future, and even though most don’t recognize his name, that’s exactly how he’d want it to be.

Eastern Treat

This feature was originally published in the winter of 2003 in Couloir, Volume XV, Issue 4. Couloir merged with Backcountry Magazine in 2006.

by Brian Irwin

Before I lived in New England my wife and I used to make an annual pilgrimage from Maryland to ski Tuckerman Ravine, on the east side of New Hampshire’s Mt. Washington. As fun as it was, it was always a little disappointing to drive 12 hours, skin for three miles, hike for an hour, and crest the bowl to find 700 people with radios, barbeques, and no fresh powder in sight. On a typical spring day the snowcat-packed trail to “the Bowl” is so crowded that it is more full of potholes than postholes. In midwinter, when the best powder is falling, so are avalanches on Tuckerman’s steep slopes. Little did we know that an hour away is a much less visited area, full of great runs, glades, and quintessential New England skiing—minus the crowds.

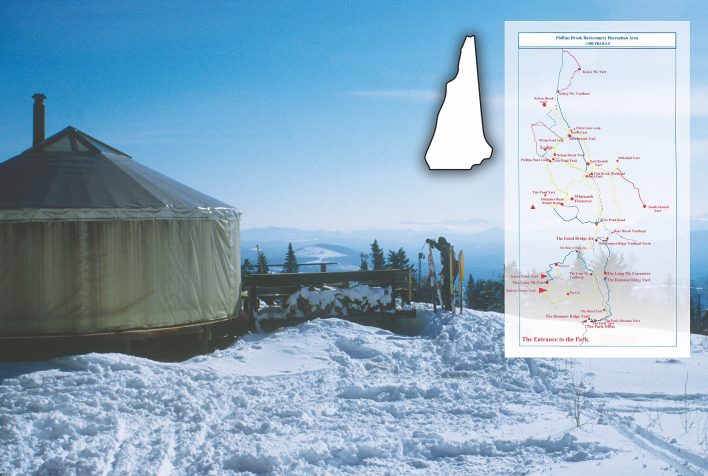

In search of northeastern powder stashes without a carnival atmosphere, we explored the Phillips Brook Backcountry Recreation area during a January full moon. Despite its association with a logging company, the Phillips Brook area is a well-preserved chunk of land, remote and beautiful—especially in the winter when the logging activity is at a minimum. The area is big—over 24,000 acres—and is owned by the International Paper company. However, it is leased to a private cooperation that manages the land tract. The area, including 75 miles of trails and 11 yurts, is comprised of logging roads (mostly inactive). Cut deep into the mountains, these trails provide access to superb eastern glades and chutes.

Driving into the gate, the snowy access road follows a cascading stream (great summer trout fishing) for miles. We encountered two dogsled teams and one parked car after 30 minutes on this road, buried under three feet of snow. Not only is there no evidence of crowds, there is also little evidence of logging. The woods are thick and clear cutting is practically absent. We were surprised to find such wild country so close to the crowded Timberland-and-Dansk-outlet lined streets of North Conway.

From the trailhead we skinned up moderate terrain to the Millsfield yurt. It sits in the middle of perfect glades. Below the yurt drip a series of narrow, steeper chutes, almost like the classic old-fashioned trails that wind with, not against, the fall line at old-school Vermont ski areas like Mad River Glen. Scattered birch groves dotted the hillsides, interspersed with hardwoods and pines—the perfect eastern blend. There were even a few cliffs to be hucked, buried in the forest.

The eastern backcountry is known for its jungle-esque density, but around Millsfield the trees were perfectly spaced, reminiscent of an American Airlines commercial showing Billy Kidd bouncing through “champagne powder” in the aspen trees at Steamboat Springs. After a day of cutting up two feet of fresh powder in this area we settled into the yurt, sharing Jim Beam and Top Ramen with two wool-clad, bearded canoe builders from Maine. We sat on the deck sipping bourbon at 2 a.m. watching the amazing green and pink ribbons of the Aurora Borealis ripple in the sky.

The next morning, in the glades, we met a group from Vermont who was passing through during a traverse. “Pretty sweet, huh?” the group leader asked.

Ben, the leader, was skiing on old wooden Tuas and well-broken-in leather boots. His soles were smooth, like a seasoned pair of combat boots (clearly pre-Vibram). He propped his bamboo poles into his armpits, brushed the snow off the bottom of his wool slacks (which he wore with neon pink gaiters), and asked us, “Been to the backside yet?”

“Nope….wait, what backside?” I ignorantly responded.

“Over the top. C’mon.”

We followed Ben and his two brothers behind the yurt, up a narrow dyke, through the thick brush, and finally to the ridgeline. It was easy to see why the yurt was built lower down; there was no view from this ridge. We continued to bushwhack for about a mile. Finally, the ridge opened up. To the east, plenty of fine lines jumped out at us as the thick trees melted into perfectly spaced glades, far from the reach of the closest logging road. All natural. Not too steep, we cut in and out, gaining speed through the glades, stomping through the thicket and letting loose again as the density decreased. We finally climbed back up to the ridge and back to the yurt, where we skied out. The trip out was almost as fun as the glades—at least 10-foot wide strips of fresh powder flanked either side of our narrow tracks up. After two miles of freshies we were back at the truck.

Returning to the truck was not the plan. Our route was going to take us from Millsfield to the Dummer Ridge Yurt, eight miles south. From there we would head west to the Long Mountain Yurt, finishing a traverse of the range that makes up the spine of the Phillips Brook. We had bottles of wine, steaks, potatoes, and ice cream in the truck for the last day of the trip, but after seeing the amenities of the yurts, like Millsfield, we were kicking ourselves for leaving the good stuff at the car and settling for dried noodles. The yurts had all the silverware, pots, and propane needed to whip up a huge feast without bringing anything but the food itself. Had I read the detailed information pack the Phillips Brook manager sent, I would have known.

Anyone who has ever done a hut-to-hut trip knows that, other than getting in turns, indulging in a big meal with wine is the most important thing. So we spent that night re-organizing our gear in the East Branch Yurt, one of the three yurts only a short walk from the access road that cuts up the middle of the wilderness area. True to hut-to-hut tradition we filled all the space in our packs (plus some)—made available by leaving tents, ThermaRests, stoves, and more—with wine, brownies, wine, steaks, and wine.

That night we had a perfect sky, clear enough to see the entire Milky Way. It was cold, but a ripping fire kept the yurt toasty. Just as we were dozing off we heard the soft, deliberate crunching of snow just on the other side of the canvas wall from our bunk. We got up and cracked the door. There, under a near-full moon, were two moose—one bull, one cow. The larger of the two must have been 14 feet tall. He was no more than four feet from the door of the yurt, staring right into our eyes. Under the bright moon his huge nostrils, big enough to shove a raquetball into, spewed steam into the cold night air.

“Grab a camera!!” Carolyn loudly whispered to me. I shifted my weight, the floor creaked, and the moose ran. We went back to bed. In the morning the whole area was trampled with hoof prints.

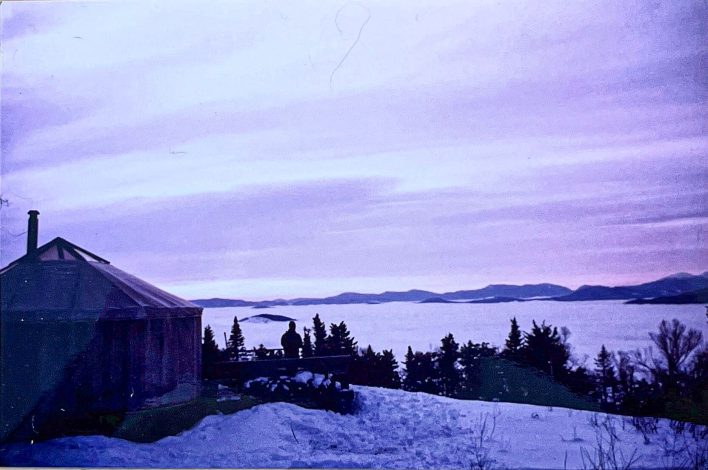

The next day we skied up to the Long Mountain Yurt, situated at 3,615 feet, the highest yurt in the area. This area had much more to offer than the previous yurt, and the setting was spectacular. A 4.1-mile ski up the Jodrey Brook trail from the valley brought us to the face of Long Mountain. Two long traverses through wide glades and we were on the ridge, looking back on the Dummer Ridge and the valley. After passing a steep chute that descends to “The Granite Shoulder” (excellent powder stashes), the trail winds through the trees emerging on the ridge’s far side. The yurt sits in a clearing that gapes right at the north face of Mount Washington, Mount Madison, Mount Adams, and the lesser peaks of the White Mountains.

Ben said this was the best skiing in the Phillips Brook drainage. He said higher elevation equaled more powder—a scarce commodity in the middle of the notorious, eastern mid-winter thaw. It was true. The snow was well over five feet deep. At least that’s how far I sunk in when I stepped off the deck to get more firewood from under the yurt. After dropping our packs we backtracked to an unmarked trail atop the ridge called the “String of Pearls Trail.” We skinned for about a mile across the ridge, heading neither up nor down. Surrounded by thick trees I was getting skeptical that this was the “classic Phillips Brook skiing,” we were told about. Thinking I was going to have to settle for a tour of the ridge, I was pleased to see the thick trees on the downslope side of the trail thin out and give way to an entire mountainside of perfect glades. I went one way, Carolyn went another, and we didn’t see each other for an hour, until we passed each other crossing a brook at the bottom. A few runs and we were back at the yurt. The sun set just behind Long Mountain and a brilliant pink lit up the heavy clouds that had sunk into the valley, leaving the snowy peaks of the Presidential Range spiking through the mist like islands in the ocean.

After our feast we headed back to the String of Pearls Trail. The moon was so bright, sparkling off the surface hoar, we never needed to turn on our headlamps. After two runs we sat down on a log to have a sip of coffee. Carolyn gripped the thermos with both hands and took a sip. Steam rolled across her face. “Listen,” she said to me. Down the hill, very faintly, we heard the firm but delicate crunching of snow.

Brian Irwin is a freelance writer and photographer based in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Also a family and travel physician, Irwin has spent the last two decades exploring the natural world and publishing his impressions. From the local Mount Washington to the spires of Patagonia, from the peaks of the Alps to the glaciers of Alaska, his adventures have been exhibited in a variety of national newspapers, magazines and medical journals. His organic, humanistic approach and realistic style have won him numerous national awards for both his writing and photography.

To read more from the untracked experience or to see our stories when they’re first published in print, subscribe.

Related posts: