One tiny, yet beautifully intricate, snowflake balanced delicately on a single strand of rabbit hair lining the hood of his coat—or maybe it was his assistant’s coat. Many details of Ukichiro Nakaya’s breakthrough discovery have been lost to the fog of time. What’s clear is that, on March 12, 1936, Nakaya succeeded in creating the first artificial snowflake in a lab just outside of Sapporo.

It had taken almost four years of careful observation, inspecting the snow crystals that buried Sapporo in almost 20 feet of snow each winter, for Nakaya to take the first step in defining snow science as we understand it today. A professor of physics at the University of Hokkaido, Nakaya’s quest to unravel the“problem” of snow was an amalgamation of his endless curiosity, rigorous scientific training and severe shortage of lab equipment for his small physics department. Trained as a nuclear physicist at Tokyo Imperial University, Nakaya was hired by the University of Hokkaido as a professor in 1930, aged just 30, when their Department of Sciences was established. Undeterred by his lack of equipment to study nuclear physics, Nakaya soon turned his attention to the as-yet-mystery of the crystalline flakes dancing outside the windows of his classroom and piling up in double- and triple-overhead snowbanks across the city.

Unlike many purveyors of snow today, Nakaya’s interest was purely scientific. Likely inspired by Wilson Bentley’s 1931 book Snow Crystals, in which the American photographer captured over 3,000 photographs of perfectly symmetrical snowflakes, Nakaya saw an opportunity to expand on Bentley’s work. In his own seminal book, Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial, Nakaya recognizes Bentley’s contribution as a great inspiration, but notes, “As scientific material, it is regrettable that his pictures were retouched and were published without details of magnifications.”

A year after Bentley’s book was published, Nakaya began taking photos of snow crystals in his lab in Sapporo. Hunched over a microscope, he would quickly snap photomicrographs (photos taken through a microscope using alight filter) of individual flakes of snow, categorizing them by shape and formation. A year later, he moved himself to the forested hillside of the volcanic Tokachidake to study at Hakugi-sō (Silvery Villa). With that, his track from nuclear physics to snow crystals was set in ice.

Despite his growing catalog of snowflakes, Nakaya’s mountainside observations could only take him so far. Unable to access the clouds where the flakes were formed, Nakaya realized he needed a lab to simulate meteorological conditions on the ground. The University of Hokkaido obliged his request for a cold room and began construction of the Low Temperature Laboratory (which would later become the Institute of Low Temperature Sciences). The lab, completed in February 1936, was crucial in Nakaya revolutionizing the world of snow science—beginning with that first artificial snowflake balancing on a strand of rabbit hair.

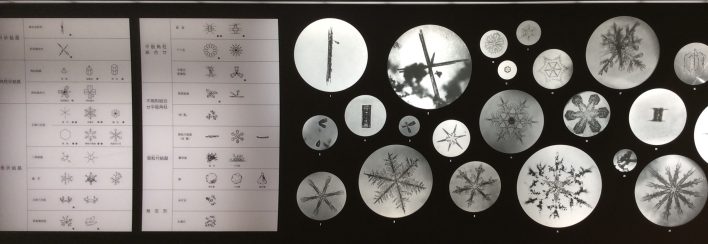

Over the following years, Nakaya and his team went on to categorize the temperature and saturation that created different types of snow, an endeavor that ultimately ended with the Nakaya Diagram. This chart, showing temperature on the x-axis and supersaturation on the y-axis, is artfully adorned with different variations of snow crystals. Almost a century later, the hand-drawn diagram remains familiar to many who have taken an Avalanche Level 1 course or studied snow crystals in depth.

Amongst all the science, Nakaya never forgot about the beauty that inspired his work. In a 1939 film on his work, also titled Snow Crystals, Nakaya called “each snowflake a letter sent from heaven.” It was a phrase he restated in his book and in many essays over his lifetime.

While poetic verses and snow science may have been his calling, the Japanese scientist was inevitably drawn into the war effort. Nakaya shortly experimented on icing and fogging in Japanese planes, working to find methods to artificially dissipate moisture in aircrafts. All the while, he continued finalizing Snow Crystals: Natural and Artificial. Nakaya notes in the book’s introduction that printing was making “slow but steady process under the adverse conditions of the War, when unfortunately the printing office was bombed and the whole copper type and original type of the text were burnt.”

In 1940, Nakaya was awarded the Imperial Academy Prize for his visionary diagram. International acclaim soon followed. In 1949, he was consulted in the creation of the Snow, Ice and Permafrost Research Establishment by the U.S. Army (now known as the Cold Regions Research Engineering Laboratory). Nakaya was then contracted as a scientist there from 1952 to 1954. His research took him to Hawaiian peaks and eventually to Greenland, where he spearheaded early investigations of ice cores for climatic research.

In 1962, after a decade of work in Greenland, Nakaya passed away following a battle with cancer. His work, both in snow and ice, laid the foundation for climate and snow science as we know it, but maybe more importantly, his careful, contemplative study percolates through history. “My father, Ukichiro Nakaya, made the first artificial snow crystal,” writes his daughter, Fujiko Nakaya. “He used to say, ‘You must listen to ice if you want to learn about ice.’ He always said that you have to be humble, surrender to nature in order for nature to speak.”

This is a sidebar from an article originally published in Issue 162, The Outliers Issue. To read the full story, grab a copy, or subscribe to read our stories when they’re first published.

Related posts: