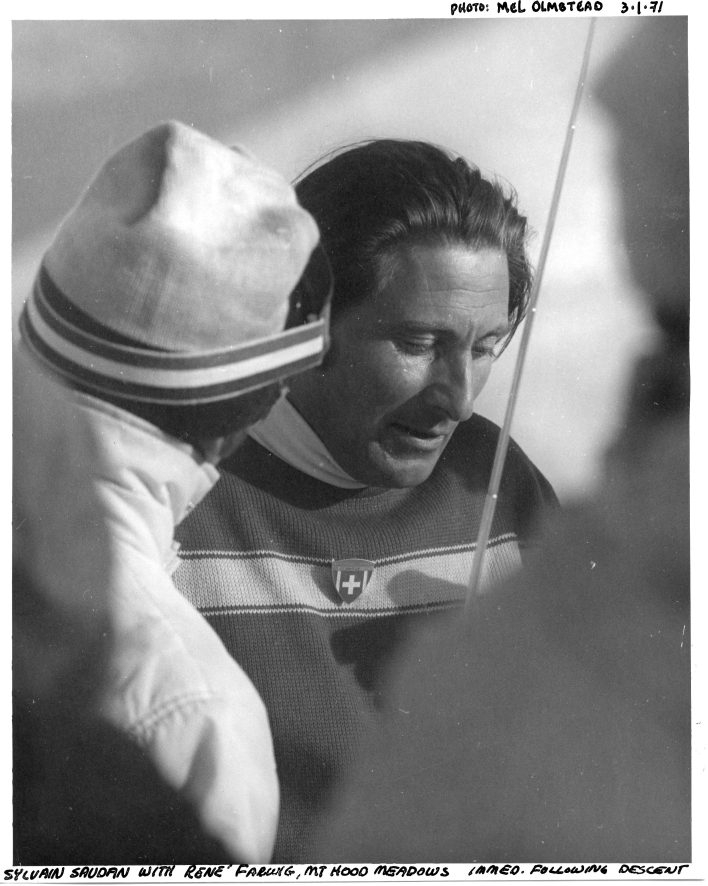

On July 14, 2024, Sylvain Saudan died after suffering from a heart attack while in Les Houches, France. Saudan, 87, was known as “Le skieur de l’impossible,” a nickname he earned for his laundry list of impressive descents. He has 23 first descents around the world, including the Eiger’s Northwest Face, Mount Hood’s Newton-Clark Headwall and the Himalayas’ Gasherbrum I. Saudan’s legacy inspired a generation of steep skiers like Bill Briggs and Chris Landry. Below is an excerpt detailing Saudan’s first descent on the Newton-Clark Headwall from Tom Hallberg’s recounting of the history of skiing in the Cascade volcanos “Turns All Year,” which was published in February 2023 in The Isolation Issue. —The Editors

In February 1971, Frenchman Sylvain Saudan flew to the Northwest at the invitation of friend and then director of the Mt. Hood Meadows ski school. Saudan was known as “Le skieur de l’impossible” for feats which included the first descent of the Eiger. His arrival in North America was about to set the steep skiing revolution, which crescendoed in the 1990s and after the turn of the millennium, in motion.

Despite his penchant for steeps, Saudan was a cautious mountaineer. He usually climbed a route before he skied it, a common practice today that allows skiers to gauge challenging sections and snow conditions. The Cascade winter of 71 had other plans. Clouds enveloped Hood, spitting snow across its 11,249-foot top, driving up avalanche danger. Saudan waited.

On March 1, the snow briefly stopped. One wouldn’t call the weather pleasant, but it wasn’t snowing. Deep, fresh drifts made a summit climb impossible in the short window, so he and Anselme Baud, a steep skiing pioneer and Mt. Hood Meadows instructor, hopped in a two-seater Bell helicopter around 3 p.m. After all, Saudan was more interested in the descent than the ascent. Wind howled at the summit, the temperature hovering around zero degrees; the helicopter pilot tried one, two, three times to place Saudan on the summit, but the elements deterred him. Four times. Five. Saudan exited, but the pilot still needed to unload Baud. Six times. Seven. Baud scrambled out, joining Saudan in the gale.

Blown free of snow, the ridge leading to Hood’s east face was a sheet of 40-grit sandpaper, but Saudan approached the Newton-Clark Headwall while Baud downclimbed toward the adjacent Wy’east Face. Six hundred feet below the summit, Saudan skied through an opening in the cliff band above the headwall. Dead end. More cliffs extended below. Side-stepping in the growing twilight, he regained the ridge and took the next entrance. It went. He arced turns on the 1,500-foot, 50-degree face before it mellowed above the Mt. Hood Meadows ski area, notching a first descent on what would later become Oregon’s only entry in the Fifty Classic Ski Descents of North America.

Of his choice to ski the headwall, and not the more forgiving south face, he told The Oregonian, “I wasn’t looking for the easy one. I was looking for the difficult one.”

This is an excerpt from an article originally published in Issue 151, The Isolation Issue. To read the full story, grab a copy, or subscribe to read our stories when they’re first published.

Related posts: