If you asked a random person in the lift line who the top splitboarder in the world was, a majority would likely say Jeremy Jones. That’s no shade on pioneers like Dave Downing or Jim Zellers, or contemporary crushers like Nick Russell, Laura Hadar or Elena Hight, but Jones has been in the spotlight as a rider for decades. His trio of movies—Deeper, Further, Higher—put splitboarding into the collective conscious for many. And his name recognition is well-deserved as he continues to push the sport forward. But even after decades in the industry, evolving from racer to freeride film star to splitboard mountaineer, he still says he’s not an expert.

Regardless, Jones has years of experience-informed insight to offer backcountry travelers and he’s compiled it in his first book, The Art of Shralpinism. The title, a portmanteau of shredding and alpinism, reveals his philosophy: that mountaineering is a vehicle for skiing the best lines in the best conditions. Part memoir, part skills guide, part almost motivational, self-help guide, The Art of Shralpinism provides a window into Jones’ evolution as an individual and an athlete. It gives readers the opportunity to learn from his lessons, lifestyle and wisdom. Before the release of the book, which came out this month, Jones sat down with Backcountry Managing Editor Tom Hallberg to talk about writing, mentorship and the mindset needed for a long career in the mountains. This interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

BCM: What motivated you to write a book, and why was right now the time?

JJ: I had gotten to know [Mountaineers Editor in Chief] Kate Rogers, and I’m a lifelong reader and writer, so I think we connected over the love of writing and reading. Then she asked to see some of my stuff and was like, “Oh, have you ever thought of writing a book?” I hadn’t, so I guess the first thing was getting over the hurdle of why me writing this book.

The motivation was that there’s a lot of amazing backcountry educational books out there, but I feel like they’re written from these professional guides and not from the perspective of that skier/snowboarder that fills these lift lines and trailheads who’s like, “I want to ride the best snow on the best lines and do it safely.” And that is the center of my education and why I do these avy courses. I don’t sit there and go, “Wow, this is so cool,” looking at snow crystals under microscopes. I want to get to the great terrain as fast as possible, do it safely and, if something goes wrong, know how to help my buddy.

So the book is really written for those people that I see in the mountains, and the heart of it is based around mistakes I’ve made, you know, this, this idea that experience is something you get just after you need it. Under that context, I’m pretty damn experienced. So ideally, you can read this book and maybe avoid some of these hard lessons that I’ve learned.

BCM: The book is part memoir, part skills guide, part almost motivational, self-help guide about how to build your mindset. How did you decide to include each of those different sorts of pieces and then decide what things you wanted to focus on in each of them?

JJ: I wanted this really approachable book that you could grab and dive in at different spots. And I think of it as these campfire stories, which are the “We went out and had this crazy experience and I’m telling the story around the campfire,” sort of stories. The mental side of things, a lot of that comes from my journal.

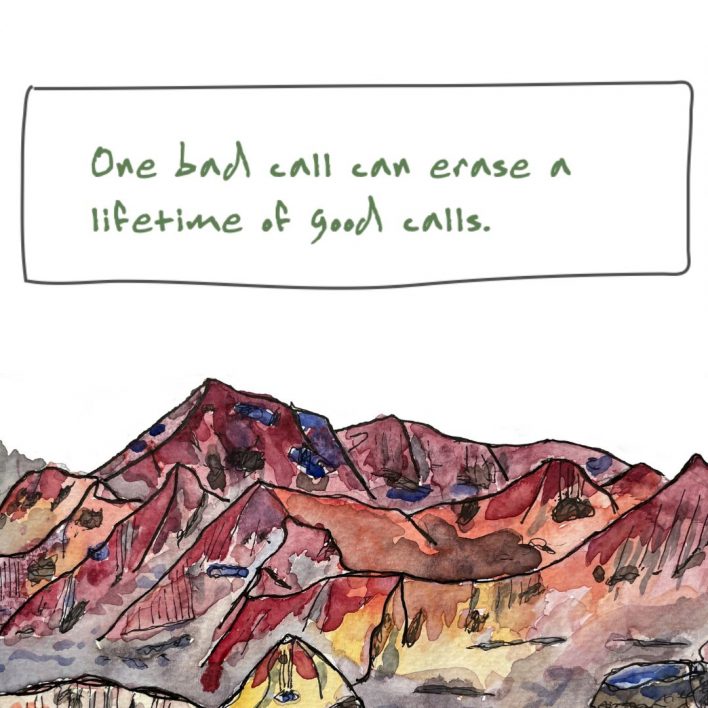

There is this huge mental component to the mountains. When you’re going into these mountains, especially like pushing your limits, it’s a real intimate conversation with yourself, you know, am I ready for this? Because it’s a zero-mistake game, and I think it’s really important to understand and not hide that. You know, you’re one mistake away from never coming home. And it happens to the best people in the world. So I like to not shy away from that thought of if we blow the call here, we’re dead. But so that’s a lot of wrestling about why you would you put yourself in that much risk. People so quickly will say, ‘Oh, you guys do gnarly stuff; I like to just do mellow stuff.”

Well, go look at the accident reports. It’s not people in front of cameras riding spine walls. I mean, yes, that happens. But my closest calls have been in mundane terrain. So many of the fatalities have been in mundane terrain. So, it’s that daily side of things, and there’s that how-to stuff, because we do train every year. And there are real fundamentals that we utilize. So the book has that mix of mental experience and just tactically here’s our playbook for going into the mountains.

BCM: You write about your snowboarding mentors. Did you have any mentors for writing this book? Did you have folks who helped you get there that you learned from throughout the process?

JJ: Mentors in general is such a huge component of this sport or lifestyle. What is special about it is that you think about the passing of knowledge that goes back from the beginning of people sliding on snow and then dealing with avalanches, it’s passed down at trailheads, around campfires, in lift lines, etc.

In terms of the book, I would say Kate was instrumental in saying, “Look, I’ve dealt with people like you before. I can help you, guide you.” And then Chris Crossen, who helped me with the book. He was very great to have just his overview of things, so I don’t totally put my foot in the mouth, and he was able to organize and bring structure to my thoughts.

It was hard, though, because I am friends with Jon Krakauer, for example, but I actually never talked to him about it because he’s such a professional book writer. I always look for people that are a little bit further down the path than me that I can relate to, but someone like Krakauer, he’s on such a different planet that I never talked to him about it.

BCM: If you had to distill the point of the book into a sort of overall takeaway or piece of wisdom for people, what would that be?

JJ: I really tried to lay out my playbook to go into the mountains as someone whose life is totally committed to riding the best lines in the best conditions and doing it day after day after day. I wanted to show my journey and the highs and lows of that and the people that I’ve purposely surrounded myself with and things I’ve learned from them. And I wanted to show the mental side of it, which is wrestling with the thoughts of, “Am I really gonna go leave my family right now and go, you know, walk into wild mountains and sleep in the snow and and put myself in incredibly dangerous situations?”

BCM: You obviously as a high-level athlete have to create structures and habits that facilitate your endeavors. You mention in the book that you aren’t fully rigid when it comes to that approach, like you’ll drink a couple beers in the evening, and you’ll eat meat every once in a while when you need to do that on a on a trip. How does that attitude help you create long-lasting habits rather than ones that you’re going to drop at some point?

JJ: To me, it’s a lifestyle, like I’m in it for the long game. I can see training for a marathon or something like that is great, but I’ve always thought I want to be doing this my whole life. I don’t consider myself like this super Type-A person. At the heart of it, I’m a snowboarder and I’m not this crazy, Ivy League, uber super-achiever, so it’s kind of like grabbing all these little things that I slowly morphed into my life that I can do day after day.

And I talked about, you know, this idea of compounding returns. Like, what are these little things that you can bring in and incorporate on a daily basis which done singularly might not mean much? I have a morning routine that’s five minutes long. One day, it means nothing. You do that two weeks, it means nothing. You do that for 10 years. It’s a huge deal. And who can’t do you know, five minutes? I mean, some days it’s three minutes. But that’s just an example of trying to really stack the deck with these simple, little almost life hacks that over time do help.

BCM: You write about being excited to ride even when the conditions are icy or low tide. How do you cultivate that mindset of wanting to go out every day and being stoked about it? Is that something that comes natural to you, or is it something you have to be intentional about?

JJ: I think it’s a natural mindset. I grew up in Massachusetts, so just going to Vermont, I was like, “Oh, my God, I can’t believe I’m here.” Then being a snowboarder that wasn’t allowed on chairlifts to then be allowed on them and go, “I cannot believe I’m taking a chairlift and I have another run to go get on my snowboard.”

It’s the same with surfing. I surf Lake Tahoe in the most desperate of conditions. I think about at the end of the day, like, “Yeah, I’d love to enjoy a beer or two,” and it’s like, “Did I earn that beer?” It always tastes better if you’ve been in the water, in the mountains. It’s about recognizing that of the over 7 billion people on the planet, you’re now out there, and I love nature’s moods and I love what I would call desperate days, where people are like, “It’s bulletproof ice.” I’m that one going to my kids, saying, “This is the best ice I have seen in the Sierra in 10 years. We’re gonna go try and ride it and turn it into a game of can you hold an edge on that ice.” Then when you find a little windblown zone you think we actually made good turns today. So, yeah, I think it’s just something I was somewhat naturally born with.

BCM: You’ve gone from racer to freeride film rider to a career focused primarily on the backcountry. How do you approach the idea of progression because you could get stuck on one of those things and stay in that realm, but you seem to always be adding new things or evolving to do something different?

JJ: Yeah, I mean, at the heart of it, I love two things. One, there’s a feeling I get when I know I’m getting out of my comfort zone. And that’s both in the mountains and in society, you know, within what I would call societal fears, and I’ve probably lost more sleep over societal fears than actual mountain life and death fears. I don’t think you get excitement without nervousness, and there’s that feeling I’ll get in my stomach where I kind of go toward those fears, because that’s where life is most exciting. And the book was a great example of going toward those fears.

I also love doing things I’ve never done before and being in those places in life we couldn’t have gotten to any sooner because you were lacking the experience and knowledge. That’s easy to quantify in the mountains, but it’s also you know, I feel like life also is going for that open space or new ground in all aspects of my life.

BCM: You talk about the mentors that you’ve had. Now that you’re where you are in the snowboard industry, do you find that role reversed? Do you find yourself mentoring folks and how do you approach those relationships?

JJ: I’d say the hardest part of writing the book was like, “Who the hell am I to write a book?” I just I don’t consider myself an expert. I feel like I’m just trying to figure it out on the daily, and I think the most effective form of mentorship is that informal deal. Inevitably I’ve maybe helped some people along the way, but I try not to be like Joe Guide Guy out there, just teaching lessons over and over again. Occasionally, I will step in if I see someone like making a call that they might have gotten away with that day, but they’re not getting away with that 10 out of 10 times. So, yeah, I don’t really have a heavy hand in the mountains, I would say.

BCM: I always find it interesting to talk to folks about the different books that they read. You mentioned a lot of authors in in your own book that have nothing to do with the outdoors. You quote business leaders and Tom Brady and other folks, so what are you reading right now?

JJ: I read a variety of different books. I have kind of gotten into more nonfiction. As someone who didn’t go to college, I do find that books have been my way of learning.

I recently finished The Overstory, which is a pretty dense book. I feel like I should get a college credit for it. But I’m looking at my nightstand, and I have Undaunted Courage from Stephen Ambrose, The Overstory, Seabiscuit, which has been nice—it’s like reading a movie. Tools of Titans, by Tim Ferriss. Yeah, I kind of bounce around, I would say. But I’ve been stuck in the nonfiction realm as of late just trying to suck up knowledge, for sure.

BCM: And I assume on some of these expeditions that you’re tentbound, do you take at least a book or two with you?

JJ: Definitely, and I have books on my phone as well. With that, I would try to go with a lighter read on an expedition just because it’s so mentally intense.

Jeremy Jones’ The Art of Shralpinism is available now through Mountaineers Books at Mountaineers.org.

Related posts: