Internationally certified mountain guide and board-certified physician Alan Oram shares how to be prepared for medical emergencies in the backcountry.

Most people see taking an avalanche course and carrying a beacon, shovel and probe as mandatory before entering the backcountry, but overlook much more common dangers: sprained joints, broken bones, hypothermia and all the other medical scenarios that can happen in a winter environment.

“What’s the most common problem that people are going to run into? It’s going to be an extremity injury, blister or someone that gets cut and they bleed,” says Dr. Alan Oram, a board-certified physician and internationally certified mountain guide. “It’s less likely that someone’s going to get caught in avalanche…. And if they do get caught in an avalanche, they have serious injuries. It’s stabilization and get out of there and prevent hypothermia.”

As Oram said, these are more common than getting buried in an avalanche and, if you’re not prepared, can be deadly.

Build Your Kit

“People bring these humongous kits and it’s like, ‘What do you think you’re gonna do with that?’” says Oram. “They forget about the simple things, like a space blanket; some kind of splinting material instead of using your pack and clothing; something to stop bleeding. Those are really the things that, if you don’t have, you’re kind of hosed.”

Instead of MacGyvering wound care with your extra puffy, and whatever you find in the woods, bring specific tools built for common backcountry injuries. This is twofold. First, improvised fixes never work as well as purpose-built ones. Second, when you’re improvising, you’ll use the resources you brought for staying warm or travelling efficiently.

Oram shared two examples of where a purpose built item can’t be replaced with an improvised fix. First is a tourniquet.

A backcountry “hack” is to make a tourniquet out of a Voilé strap and a ski pole, twisting the pole to tighten the strap. But is it a good idea to try a Five-Minute-Craft fix when your friend is bleeding out? “Definitely not. Bad idea,” says Oram. “You need a commercial tourniquet. They’re tried and true.”

The second is splinting. Oram says that there are a thousand ways to make a splint, but many of them involve ski poles and jackets: “I’d rather somebody would carry a SAM Splint in their pack than start rifling through your pack and taking stuff out that you need to ski with.” A SAM Splint is a foam-padded strip of aluminum that can be rolled up and stored in a first-aid kit or laid flat and stored along the back panel of a pack. It’s stiff enough to hold a joint in place, but malleable enough to comfortably mold around an injury.

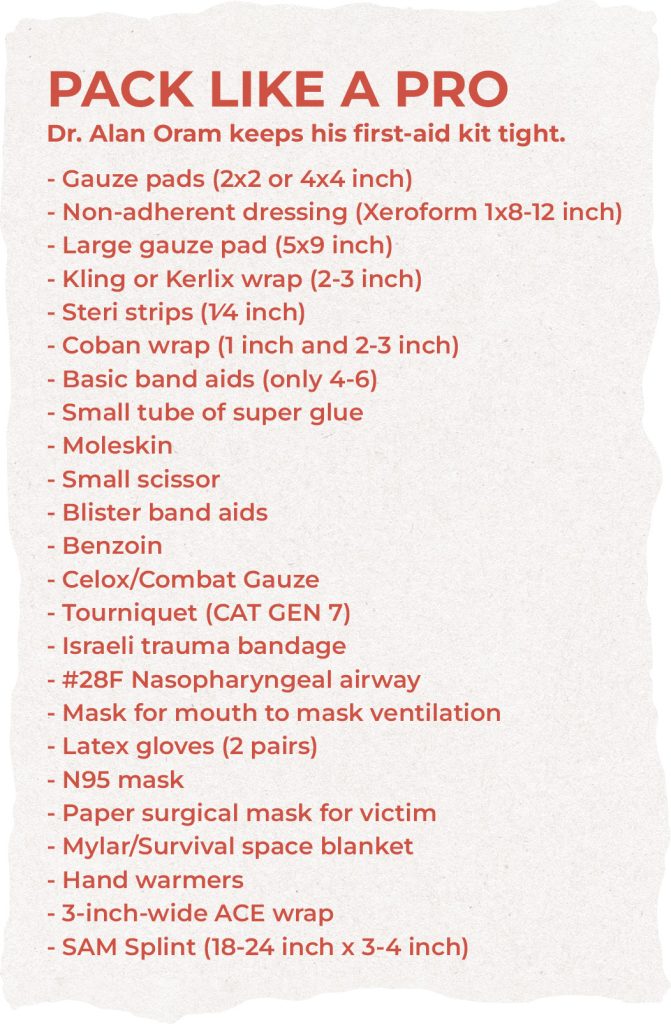

When he showed me his first-aid kit, most of it fit in a zippered pouch that was just larger than a Nalgene. The secret to keeping it compact is knowing what you need and what you don’t. He advises leaving out the safety pins, caveat wraps and giant box of Band-Aids that come in premade first-aid kits. “Just simplify it,” he says. “It’s easy to build your own and I think it’s more usable.”

Know How to Use It

While Oram went through medical school and residency, there are other education options for getting backcountry first-aid basics. “At the very least, people should have a Wilderness First Aid (WFA) course,” says Oram. These 16-hour courses are widely available in the U.S. and cover everything from splinting to altitude sickness to hypothermia.

When deciding which one to sign up for, consider looking for one taught by a ski guide or in an area with a large backcountry ski scene. While the curriculum will remain the same, an instructor in a desert climate will likely spend more time on what their students are most likely to encounter—heat rash and snake bites—whereas a mountain town course might focus on cold injuries, head trauma and broken bones.

Further education could be a weeklong Wilderness First Responder course, but Oram says that for the average recreationalist, a WFA and practice is plenty.

Rescue Response

After stabilizing a backcountry injury, the next step is evacuating. But it’s not always as simple as skinning back to the car. Depending on a number of factors like weather, location, time of day and the injury itself, you could be self-evacuating, hunkering down for a night or calling search and rescue.

“The things that people need to know when they’re calling for help with limited communications are where you are, what the problem is, what you need. Those are the three,” says Oram. “There’s so many variables that it’s hard to give a laundry list, but the key is being in a place where you can communicate.”

He adds that, before entering the backcountry, it’s important to know who you’re calling. Sometimes it’s a professional search and rescue team, sometimes it’s the local sheriff ’s office or the local land manager. Additionally, knowing how you’re going to communicate is important. “What do you have to communicate with? That’s going to be an InReach or phone or whatever. Just know it, know where you are and what’s going to work. You might be super remote,” says Oram.

If there’s bad weather, it’s late in the day or a rescue team isn’t available, you will be hunkering down or self-evacuating. “If you’re just two people, you’re not going to be able to drag somebody out in a sled. This is not possible, but it is possible to make a shelter, put somebody in it, and then you can go for help and then come back,” explains Oram. “Ski tarp, rescue sled, anything like that. Somebody in the group should have one. That’s one of those basic things.”

Fight Complacency

When Oram asks me if I always carry a rescue sled, I sheepishly reply, “It depends.” It’s a good reminder that, just like when evaluating avalanche slopes that we ski often, it’s important not to get complacent with the emergency gear we carry.

Oram circles back to being prepared for the worst: “What if somebody has a lower extremity injury, and they can’t ski, and you’re 5 or 6 miles out? What are you going to do? Search and rescue is not always available. Weather might be limiting. It might be an area where there just simply aren’t the resources to do that, and then you’re stuck and you’ve got to deal with it.”

This article was originally published in Issue 161, The 30th Anniversary Issue. To read more from the untracked experience, grab a copy, or subscribe to read our stories when they’re first published.

Related posts: