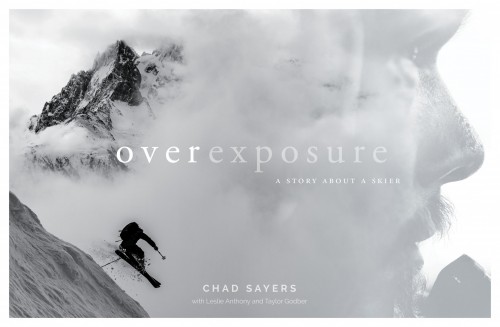

Editor’s Note: This chapter was taken from Chad Sayers’s book, Overexposure: A story about a skier, in which Sayers shares iconic trips and photography while stripping down his life as a professional skier to the bare bones.

ONE TRANQUIL EVENING, cradling a cup of tea on my porch in Whistler, a voice within me spoke in what felt like desperation: Why don’t you just move to La Grave for the winter?

I didn’t hesitate in answering.

A shift in the rhythm I’d been living made sense. During seemingly endless missions chasing storms around the world and filming for A Skier’s Journey, I had accumulated injury after injury. Short off-seasons of only a few months didn’t deliver enough time to fully heal, and the compounded chronic pain had become almost too much to bear. My body felt shattered, and along with it, sadly, my will to ski.

The isolated village of La Grave in the southern French Alps had always beckoned for a longer stay. From my first visit—inspired by an image in Powder Magazine of American skier Doug Coombs traversing the heinously steep Pan de Rideau—I felt I would live there one day. And in that moment on my porch in Whistler, it seemed the perfect place to seek the kind of solace and inspiration I needed to continue skiing.

The move to the Alps would indeed bring light into my soul, but it would also usher in one of the darkest periods of my life.

WALKING THE EMPTY, cobblestoned streets of Ventelon for the first time, I immediately felt the return of my ski spirit. This village of only fifty souls, perched fifteen switchbacks above La Grave, felt minuscule compared to the windswept glaciers hanging 2,000 meters above it on the legendary ski mountain of La Meije—it was easy to see from its elevated vantage how exposed, unpredictable and humbling that peak truly was. With La Grave poised to be the arena that saved my skiing, it seemed the perfect base.

I rented a quaint loft apartment in a 16th-century stone house—apropos given that everything else in Ventelon seemed to have paused in time around the same era. The town’s pace was conducive to savoring an espresso, making time for conversation, walking instead of driving. Above all, folks lived the same ethos as the valley’s earliest settlers: with a passion for the mountains.

While I shared much adventure in La Grave with many amazing friends, I also spent a significant chunk of time keeping to myself. I could take in an unobstructed view of La Meije through a set of French doors to my balcony. On clear, star-filled nights I’d lie on the heated brick floor, gazing through a skylight; other times I’d watch candlelight flicker on the ceiling as I embraced the sound of storms that sometimes raged for days. The seclusion was exactly what I craved.

When the weather calmed enough, I’d ski down to the village through winter’s raw howl, sliding down streets, dipping through alleyways, passing locals tending livestock as the smell of home fires, swirling in the chaos of wind, delivered a strange sense of comfort.

For a while, this was home.

While I shared much adventure in La Grave with many amazing friends, I also spent a significant chunk of time keeping to myself.

LE TÉLÉPHÉRIQUE—an odd, pulse-style cable car with groups of five gondolas linked together—was the means to gain 2,100 meters of vertical from the village of La Grave. At the summit station, a 360-degree view took in the peaks of Belledonne, Thabor and Aravis, as well as the Mont Blanc massif. A few steps farther put you atop the Girose Glacier and myriad potential descents.

Uncontrolled and unpatrolled, there were no signs in La Grave marking cliffs or rocks, just a civil demand that you have your backcountry wits about you: If you weren’t competent enough to rescue yourself in the event it became necessary, or you hadn’t hired a guide, you had no right stepping into your skis.

I learned much about these mountains from the phenomenal souls with whom I shared memorable days: Canadian expat Ptor Spricenieks, American ski guide Joe Vallone, Swedish ripper Lars Krantz and my cherished friend Josefine, mother of two and wife of local guide Per Ås.

We sailed through the mountains and surfed between the walls of endless couloirs, hearts pumping, breathing hard, ever-present in the quest to stay upright. Diving from snow pocket to snow pocket, dodging crevasses, disappearing into powder explosions—popping out with just enough time to set a mark for the next safe turn before vanishing again. Skiing La Grave was a soul dance, your partner the ever-present possibility of death.

When these mountains spoke, it was imperative that you listened. Sometimes the messages were obvious—a massive avalanche ripping down the face of La Meije, or a serac breaking off a glacier as you skied by. Other times it was more a whisper in the midst of a storm, or while stuck in the crux on a wind-hammered traverse, thinking of all who’d died before us on this ledge, peering down at the same exposed rocks.

Was it faith, fear or skiing with an intuitive heart that kept us alive? None of us was sure, but I learned fast that if you didn’t respect this sacred place, you weren’t long for this world.

WHILE LA GRAVE was good for my soul, other forces were conspiring to take me down.

Scanning my weathered skin and wrinkled face, I saw the ravages of the elements etched in the mirror, as well as the ongoing pain from years of self-inflicted injury. That young, fresh-faced skier from Silver Star had disappeared and I wondered who I had become.

Mistreatment had brought my body to a point that I often couldn’t walk to the téléphérique without my left leg screaming Go home before something terrible happens! Yet I continued to prioritize skiing above other forms of happiness or comfort that could free me from the turmoil—such as my girlfriend at the time. We’d met in the surf in Costa Rica and had been riding out the usual romantic ripples of a long-distance relationship. We spent months in the tropics together in the off-season and she had visited La Grave a few times. Like any partnership, it demanded attention, more than I was willing to offer up at times, because skiing was everything to me. Or at least I believed so.

Just like the early days on Blackcomb Mountain, starting at the top and stopping at the bottom was my jam here. No standing around or pausing halfway. Just going fast, accelerating in the difficult spots, navigating by instinct. While my ongoing physical discomfort was tempered by the adrenaline of descent, it always surged back when I stopped, often crippling me to the point that I would only make it as far as the floor of my apartment, where I might then lie for hours. My mind felt clear with so much space in which to be still, but my body was overwhelmed, confused and tired.

And of course I was still a working pro, expected to be available when asked. In preparation for out-of-town film trips, I’d slip into one of the stone troughs near the church, ancient vessels that overflowed with ice-cold water from the mountains. The deep resonance of the church bells brought serenity while the water numbed my body—along with swirling yin-yang thoughts of skiing for the cameras again. I dreaded having to leave La Grave to “work” at skiing, though staying wasn’t supporting my healing either.

Was it just the issue of physical injuries, or was my body also starting to reflect this inner conflict? Whichever it might be, it was reshaping the cadence of my descents, and the harsh reality was that for the first time in an 11-year career, I was literally fighting to stay on my feet. I knew I couldn’t stick to this routine, but I also couldn’t find it in me to walk away.

Off balance and riding the tails of my skis, physically drained from overthinking and not sleeping, nothing felt quite right. Yet this mission had been meant to heal all that ailed me—to literally save my soul.

“IT’S OVER!” Her words rang in my ear through the phone. Our love hadn’t been strong enough to survive the long stretches of separation, and I couldn’t give up skiing to move to the tropics.

After weeks of emotional anguish, I woke up one morning and decided to ski a La Grave classic with a few friends—a 2,150-meter couloir-studded run that included a technical rappel 1,400 meters downslope of the entrance. Conditions were in top form: a cold, tight snowpack with 15 centimeters of fresh snow on top. Taking the lead, I dropped in but skied haltingly, scared to let the surface snow run. Off balance and riding the tails of my skis, physically drained from overthinking and not sleeping, nothing felt quite right. Yet this mission had been meant to heal all that ailed me—to literally save my soul.

The top section skied well, but as I descended towards a large rock concealing the rappel anchor, I realized the couloir had frozen up. Soon it became too dangerous to ski, and I began to carefully sidestep my way towards the anchor, now 100 meters below. Unroped, at each downward step I plugged a finger into the hard snow as a lifeline until, 10 meters from the rock, the snow met blue ice. A fall here meant a 600-meter death ride. Was I going to try and be the hero or listen to intuition and sidestep back up? It was a defining moment.

So, God, I thought. What do you think of this one?

The only answer was the sound of my breathing.

Gingerly, I stepped out on the ice. Sure enough, my ski slid out and I was left dangling by a finger. Though I’d had no intention of going for it, and would, in fact, sidestep up to build a new anchor where we could lower ourselves to the main anchor and safely navigate the couloir’s crux, I had needed to experience the feeling that I wasn’t in control of my life, my mind or the path ahead—the stark line between the end of everything or the chance at a new beginning. And in that moment, I knew: I had to hang up my skis, get out of town and sort myself out.

Chad Sayers is a skier, surfer, climber and photographer. He has spent the last 23 of his 42 years inside the belly of the best that is professional freeskiing competing, ski mountaineering, adventuring and experiencing ski culture in the far-off corners of the winter mountain world. Through it all passion and spiritually have marked his path. When not jet setting, Sayers makes a home in Whistler, B.C.

His new book, Overexposure: A story about a skier, comes out on October 1 and is available for pre-order here. It was written with help from Les Anthony (editor), Taye Godbur (co-writer) and Amelie Legare (design.

Related posts: