On Leap Day 1936, as Spain descended into civil war and Hitler prepared to march troops into the Rhineland, a group of Californians set off from Yosemite Valley for the High Sierra Nevada. They carried heavy wooden skis and 50-pound packs, aiming to make the first winter ascent and descent of 13,114-foot Mt. Lyell, Yosemite National Park’s highest peak.

Among them was 23-year-old David Brower, who would eventually become one of the 20th century’s most influential environmental activists. He’d spent the summers of ’33 and ’34 backpacking the range, drinking from streams, honing his technical skills on dozens of impressive first ascents and leaving his signature atop more than 70 peaks.

“I would never again be so self-reliant in the wild for so long,” he wrote decades later, “or see so few people there, or be so totally absorbed in exploring and enjoying and so unconcerned with protecting the wildness that had made the experience possible.”

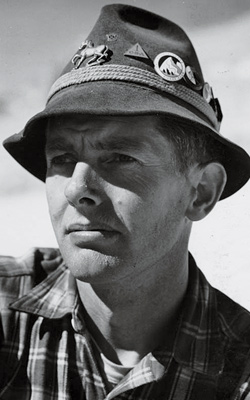

Portrait of a young David Brower courtesy Colby Memorial Library, Sierra Club.

As a 77-year-old looking back over six decades of bitterly contentious environmental battles, Brower would see that, already in the 1930s, there’d been only a handful of places left where a person could get more than 10 miles from a road. “I had not yet understood what wilderness means or what the threats were to the last vestige of it,” he wrote. “I was low and slow on the learning curve.”

Ski mountaineering—for pleasure, rather than for sheer expedience—was a relatively new activity in the 1930s. For young Brower, it provided an incomparable means to experience that wildness he’d come to think of as his true home. After an epic march, a hurricane-force wind event and a roped, five-man simul-scramble up a “final sixty-five-degree pitch of snow and rock,” the 1936 crew made the summit of Lyell. They soaked up a seemingly endless view of snow and vertical granite, then schussed 7,000 feet down to camp.

Brower started full-time work for the Sierra Club in 1939 at part-time wages of $75 per month. He dove headlong into the campaign to designate Kings Canyon a national park. During the war, he served as an officer and instructor for the 10th Mountain Division, influencing thousands of young Americans in their attitudes toward the mountains. He was there in the Apennines to help drive the Germans from Italy and afterward went north to the Matterhorn and Mont Blanc.

What he found there appalled him. There were cow trails, roads and buildings everywhere; power plants and mines dug into the range’s deepest recesses. He sent home a piece for the Sierra Club Bulletin in 1945 entitled How to Kill a Wilderness. “The Alps had been explored and enjoyed to death,” he later wrote, “and I moved from the battle against Hitler to the battle against despoilers of wild places.”

Two years ago, my father gave me his old copy of Manual of Ski Mountaineering, a compact 1947 edition with a waterproof cover. I was surprised to see David Brower’s name on the frontispiece as editor, opposite a photograph from 1941 of a pair of graceful arcing ski turns at the base of Bear Creek Spire.

I’d just signed on part time with a small organization dedicated to protecting the few remaining wild places in North America on behalf of a growing contingent of backcountry skiers and other winter mountaineers. It was the last year of Obama’s presidency. There’d been a resurgence of anti-federal, anti-environmental Sagebrush Rebellion activity, manifest most notably in the armed takeover of Oregon’s Malheur National Wildlife Refuge. In county and state governments across the West, and in the U.S. House of Representatives, men (and some women) were dedicated to selling off or otherwise wringing short-term profit from public lands.

This undated photo is said to be of David Brower on a “snow bridge across Illouette Creek, Mt. Starr King trip.” It was published in the “Manual of Ski Mountaineering” in 1942. Courtesy of Colby Memorial Library, Sierra Club

On the other hand, there’d begun to develop an encouraging coalition of outdoor companies and human-powered recreationists whose primary order of business, at the time, was to give Obama’s administration ample cover to use the Antiquities Act to protect a swath of federal landscape in southeastern Utah under the working title of Bears Ears National Monument.

I’d been aware of Brower as an environmentalist, as the man who’d transformed the Sierra Club from a local outing club into a powerful national force for environmental defense. I knew of the battles to save Dinosaur National Monument, the Grand Canyon, the Redwoods, Mineral King and the North Cascades, and of the heroic work leading to the 1964 passage of the Wilderness Act. I also knew of his failure to oppose the re-routing of the Tioga Road and the heartbreaking loss of Glen Canyon, failures he never forgot. Somehow, I’d not quite registered that Brower had first been an accomplished rock climber and skier.

But now, in the midst of our current government’s crusade to dismantle more than a century of hard-fought protections for our ever-diminishing wild places, and with a clearer understanding of the high stakes and daunting challenges, I find myself coming back to Brower.

He never forgot the wildness he’d first experienced in the 1930s in the High Sierra. And as he grew older, to the chagrin of some of his more moderate friends and colleagues, he grew more radical and uncompromising in his allegiance to those places. Is it not now incumbent on us to do the same? As backcountry skiers and riders, we know precisely what’s left of the wild in this country. Will we be the ones to save it? Or will we let it go?

An award-winning freelance writer, David Page is advocacy director for Winter Wildlands Alliance.

Related posts:

Mining for Turns: A planned hut system outside Breckenridge, Colo. aims to offer access to a little …

Giant’s Steps: A Brief History of an Infamous High Sierra Line