In the October issue of Backcountry Magazine, atmospheric scientist Alan Betts talks about the implications of climate change on wintertime precipitation in Japan. And while the status of Japan’s snow is important, it’s part of a larger global-climate equation. So to get the lowdown on a bigger atmospheric picture, we followed up with Betts to learn more about his predictions.

Betts, an independent scientist funded by the National Science Foundation for over 30 years, explains on his website that his research is dedicated to understanding “how climate change is affecting the Earth; the northern U.S. states and how we might respond to it.”

When asked about climate trends, Betts does not tell a story of doom and gloom, but he does emphasize the role variability will play in years to come. We caught up with him at his home in Pittsford, Vermont to hear what he had to say.

[aesop_quote type=”pull” background=”#ffffff” text=”#000000″ width=”100% content” align=”left” size=”2″ quote=”If you run forward 10, 20, 30 years, we actually have no idea what kind of fluctuations between these extremes we are likely to get.” parallax=”off” direction=”left”]

Backcountry Magazine: What are some of the global climate-change trends you are seeing?

Alan Betts: What’s happening—or at least appears to be happening because we can’t pretend to know the full extent of these trends—is that these climate extremes are getting larger, and they are getting larger on a global scale. Just look at the contrast between last winter and this past winter. The change to the Northeast is huge between the last two years.

BCM: How does snow cover affect our winter climate?

AB: Traditionally, people thought that it snowed when it was cold, which is true, but there is a feedback in the climate sense—when you get snow, the temperature plunges. The difference between snow and no snow in winter temperatures is pivotal. For Vermont, when we have a winter with little snow cover, it is automatically 10 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than in winters where we have solid snow cover. What is going to happen as we move forward in the short term is that the number of days with snow cover will drop, and the average winter temperature will go up more or less linearly with the drop in snow days.

What’s difficult for the ski industry and difficult for people to grasp is that there is a switch in this transition. Snow versus no snow is a big difference in temperature, and if you don’t have the snow on the ground already, then the new snow that falls is likely to melt. It’s hard to melt the snow if you’ve got it, but if you don’t have it, it is hard to get into that snowy state and stay there.

[aesop_content color=”#000000″ background=”#ffffff” height=”500px” columns=”1″ position=”none” img=”https://backcountrymagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/2016_temp.jpg” imgrepeat=”no-repeat” imgsize=”676″ floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”down”]This climate map from noaa.gov illustrates how 2016 has experienced the warmest average temperatures on record.

[/aesop_content]

BCM: Explain some of the climate trends you have seen over the past few years.

AB: When people talk about climate change, and they run models, all they really get out of them is that there are some broad trends projected into the future. But the trouble is that nothing changes smoothly in the real climate system. We have been puttering along with the global temperatures not going up very much for about 10 years, and then along came the El Niño last year, and the temperatures jumped on a global scale by something like a half a degree Fahrenheit, which is the most that it has ever jumped.

The other thing that is happening—we don’t have a good handle on it—is that there are stationary wave patterns in the climate that you could see in 2015. For three solid months there were cold temperatures across the eastern U.S. and Canada.

Everywhere else, it was quite warm. Alaska almost had warmer temperatures than eastern Canada that particular January, February and March. Here on the East Coast, we got huge amounts of snow that stayed.

Regional precipitation ranks in the U.S. for the first part of 2014 as shown by noaa.gov.

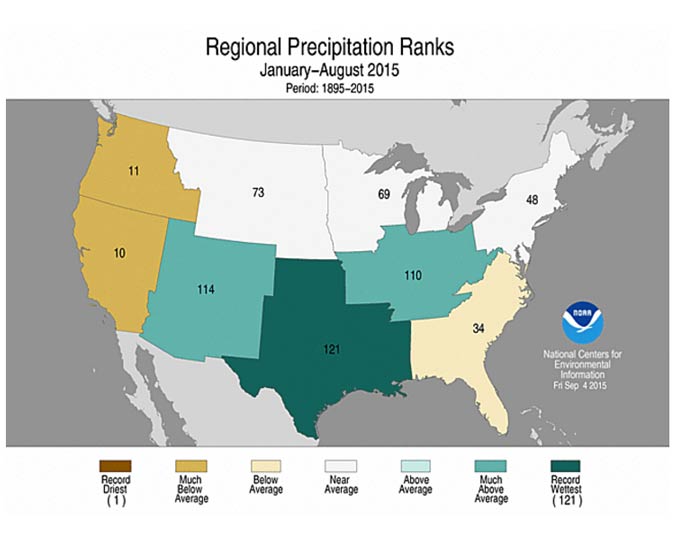

Regional precipitation ranks in the U.S. for the first part of 2015 as shown by noaa.gov.

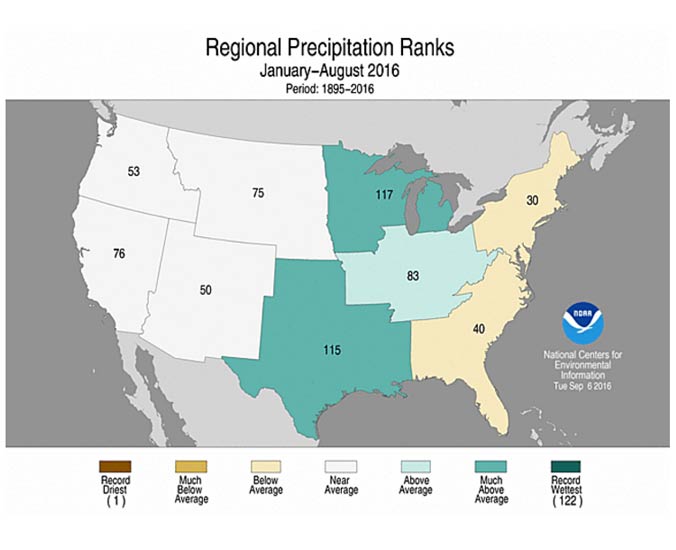

Regional precipitation ranks in the U.S. for the first part of 2016 as shown by noaa.gov.

The only difference in the East between 2015 and 2016 is that the cold area over the continent simply disappeared, and the whole of North America was warmer, as well as all of Eurasia.

[aesop_quote type=”pull” background=”#ffffff” text=”#000000″ width=”100% content” height=”100″ align=”left” size=”2″ quote=”These climate extremes are getting larger, and they are getting larger on a global scale.” parallax=”off” direction=”left”]

BCM: What will climate variability look like in the future?

AB: If you run forward 10, 20, 30 years, we actually have no idea what kind of fluctuations between these extremes we are likely to get. We are starting to see that in the last decade or so; these extreme swings have increased a lot and they have led to strong precipitation and flooding. They are leading to these extremes in winters. The jet stream patterns that used to flow fairly regularly at substantial speeds from west to east have frequently slowed, and the weather patterns slow down with them.

And generally speaking, patterns on a global scale are changing. For winters moving forward, expect greater extreme winters with lots of snow and winters with very little snow. We will see transitions where, if we lose the snow, we can lose it all. Going forward, yes, it is likely that we will get more rain events, and certainly at some point in this next century, winters without snow will become common.

If anything, the changes appear to be accelerating and shifting into more extreme states on a global scale than models are predicting, but you can’t generalize from just five or 10 years of this behavior.

This past spring, for example, it’s was so warm in the Arctic that the Arctic sea ice was melting on a scale that has never happened before, and we had no idea what that would do to our weather this year. But then the Arctic weather got colder and this September the sea-ice cover was only the second lowest on record. But in the northeastern U.S., we are again moving into a warm fall.

[aesop_quote type=”pull” background=”#ffffff” text=”#000000″ width=”100% content” height=”100″ align=”left” size=”2″ quote=”For winters moving forward, expect greater extreme winters with lots of snow and winters with very little snow.” parallax=”off” direction=”left”]

—

Alan Betts of Atmospheric Research in Pittsford is a leading climate scientist. He is a frequent speaker on climate change issues who has worked on climate-change planning for Vermont. You can read his columns for the Sunday Rutland Herald, and see his radio and TV interviews at alanbetts.com.

The climate map from NOAA is labeled June so how can it represent 2016 which is not even over? Can NOAA even be trusted? Bad data, bad models. Few are talking grand solar minimum and there seems to be mass denial of ongoing geo-engineering.