In spite of the prominence of New Hampshire’s Tuckerman Ravine as a classic spring-skiing destination, the U.S. Forest Service has closed access to Mt. Washington’s east side and the Mt. Washington Avalanche Center has ceased forecasting for the season, instead urging visitors to stay off Mt. Washington in accordance with New Hampshire’s Stay at Home order that’s part of the state’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. While it’s not quite the same as a spring day spent in Tucks, Backcountry’s Boundless Issue (#133) features a 24-page deep dive into the history of skiing on Mt. Washington—purchase a copy of the issue now at shop.holpublications.com with free shipping or download the digital version for just $3.50.

Here’s an essay that’s excerpted from the feature.

About a decade before I ever skied on Mt. Washington, several friends and I were climbing out of Tuckerman Ravine on the Boott Spur Trail on a cold April morning when we heard an explosion that echoed off the walls of the glacial cirque. We later found out that near the Hermit Lake Shelter, a U.S. Forest Service Avalauncher had misfired, causing an explosive round to ignite in the device’s barrel, injuring two snow rangers and a bystander. Much later, I learned this mishap set back the development of the gas-powered launcher, used to lob explosive charges into inaccessible snowfields for avalanche control. Avalaunchers are widely used today but were experimental back then in 1966.

Hiking into the ravine in the memorably snowy winter of 1969, you couldn’t avoid seeing the avalanche swath ripped out of the sub-alpine forest of Lion Head that crossed the Tuckerman Ravine Trail. In May 1972, I happened on the aftermath of the explosion that destroyed the second Tuckerman Ravine Shelter and watched a USFS Thiokol head down the trail carrying 55-gallon drums holding only long, charred strips of steel, all that remained of the hundreds of skis checked by their owners in the basement of the AMC-run shelter.

Oblivious to these glimpses of calamity, I took up the habit of spring skiing in the ravine in about 1975. As a ski shop mechanic in 1977, I was skeptical of the claims of Salomon binding reps that their new ski brakes would stop a released ski on the hill—until I took a fall on the Center Wall, slid to the angle of repose, then had to kick steps back up to retrieve the ski at the site of my fall. I recall 1978 in particular as a spring when I couldn’t tear loose from ski trips to the ravine, delaying the start of a new summer greenskeeping job long enough to deserve a major chewing out from the boss on my first day of work.

Years later I somehow landed as executive director of the New England Ski Museum, presumably helped by my seemingly random work history as a ski mechanic, patroller, landscaper, state park ranger, et. al. that fell into place as appropriate prerequisites for the unique role of curator of a museum about ski history. It took another year or so to realize that a familiarity with the White Mountains, AMC and Mt. Washington were also major qualifications for grasping the ski history of New England, as all were central to the evolution of the sport in the 1930s and 1940s.

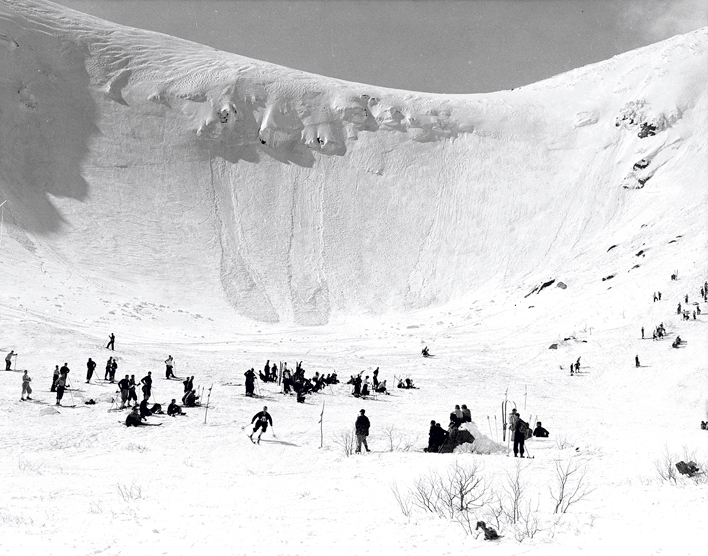

Anyone wanting to ski in the East in April in the days before snowmaking probably had to make the hike into Tuckerman Ravine. Forester Henry Ives Baldwin was one of the first to publicize the ravine as a spring skiing destination when he wrote an article about a June 1926 trip in the AMC’s journal. Baldwin’s editor rejected his photos showing mostly snow and little else for their lack of contrast. The hard snow remnants of the winter of 1926 would not completely melt away in the ravine before the first snowfalls of the winter of 1927 arrived, a phenomenon not observed since.

The three-mile distance from the trailhead to the gullies and bowl of the ravine did not limit access by thousands of skiers, nor did it bar fashions in ski culture. Skiing in Tuckerman closely mirrored, and sometimes prefigured, trends in Eastern skiing generally. Competitions in the ravine in the 1930s were as popular and as hair-raising as the downhill races that were causing growing casualty lists on the narrow CCC trails of the day. The first American giant slalom race, held in Tuckerman in April 1937, introduced a new, less hazardous format that would be widely adopted.

Brooks Dodge’s 1940s pioneering ski descents of more than half of the recognized ski routes in Tuckerman—including the most daring and difficult of the gullies—were some of the earliest instances of a mode that only decades later would be called extreme skiing.

Evolving ski equipment quickly turned up in the ravine. In 1950, Howard Head, after 39 prototypes of his metal skis did not prove out, sent 10th Mountain veteran Clif Taylor to ski the Headwall, where Taylor declared the 40th model a great success. Not long after the 1970s rediscovery of the telemark turn by Nordic skiers in places like Lake Placid, N.Y. and Crested Butte, Colo., tele skiers turned up in the ravine. Snowboarders followed in the 1980s, and AT gear is now ubiquitous on the Presidential Range.

Equipment, clothing, techniques have all changed since the ravine was first skied. What does not change is the ski experience, and it is fair to say that in Tuckerman Ravine, skiers today can approximate the experience of the pioneers— the workout of the uphill approach, the uncertainty and exhilaration of the fast-pulsed downhill drop and the sense of fulfillment brought by a day on skis in the majestic, decidedly non-Eastern, alpine landscape.

—

Jeff Leich has been executive director of the New England Ski Museum since 1997 and serves as the editor of the Journal of the New England Ski Museum. He’s authored two books, Tales of the 10th: The Mountain Troops and American Skiing and Over the Headwall: The Ski History of Tuckerman Ravine. Leich and his wife live in North Conway, N.H. and have two adult children, both of whom are far better skiers than their parents. This essay first appeared in Backcountry’s Boundless Issue (#133).

Regards Jeff,

Could you forward me any more information on the Tuckerman Ravine avalauncher incident? It is something that I am aware of, but could never find much detail about it. A friend and I collect vintage avalaunchers. We have a rebuilt and working 1960 Fireball, a 1967 Mark 16, as well as several XM 2000 series guns.

Hi Paul, You should be able to find Jeff’s contact information to learn more through the New England Ski Museum. If you’re unable to track him down, please email one of our editors and we’ll help you out.

What ever happened to Bosco, Famous singer/guitar player at HoJo’s nights ??? In the 60’s. Thanks, steve colby

Unfortunately Paul ”Bosco” (close friend of mine) passed-away a few years ago in Boseman,Montana!