Growing up in New England, I never imagined our few 5,000-foot peaks could be the backdrop of that scary headline, “Avalanche Buries Skier.” Only ever having seen avalanches on TV, they felt distant. Earlier last year, however, I realized just how wrong I was when I read that a man had been airlifted from New Hampshire’s Mount Washington due to a life-threatening injury he sustained in an avalanche. As a rookie in the world of backcountry skiing, I suddenly felt uneducated and naive.

Thankfully, that Mount Washington skier overcame his injury, but many don’t. On average, there are 27 avalanche fatalities nationally per year. Last winter alone, 30 people died in the U.S. due to avalanche-related accidents. With backcountry skiing and riding trending as the fastest growing segment of the industry, experts in the fields of snow science and public health are recognizing the importance of education in ensuring safety in avalanche terrain. In tightknit mountain communities, panelist-led discussions are fostering safe snow practices locally. At the national level, studies done by the American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education (AIARE) confirms the importance of avalanche education. After completing courses in avalanche education, students have an increased likelihood to perform proactive safety measures in the backcountry.

This fall, I was introduced to avalanche education when I attended the “Avalanche Forecasting: The State of the Art” forum on snow safety in Stowe, Vermont. Without any clues as to when the first flakes of the season would fall, a crowded room of attendees, and a panel of experts in the field of snow science, eagerly engaged in discussion over the upcoming backcountry ski season. Amidst presentation slides delineating how to identify avalanche terrain and interpret avalanche forecasts, panelists continually returned to the human factor.

“We have airbags and beacons and shovels; we’ve got all these awesome tools,” panelist Jeff Fongemie says. “But most of the time it comes down to human error. It’s the humans that are making mistakes.” The director and lead snow ranger at the Mount Washington Avalanche Center in New Hampshire, Fongemie found that avalanche fatalities often share one commonality: human errors in decision-making.

Randy Trover, another speaker at the forum and the former snow safety director at Utah’s Snowbird Resort, recalled that it can be a point of pride for many skiers who dismiss the safety factors used to judge difficult lines in favor of being able to say, “I went up and skied it anyway.” In avalanche terrain, Trover urges skiers and riders to do the opposite, saying, “Don’t be afraid to go somewhere else [if the snowpack looks weak]. It’s so easy to be wrong.”

This past October, a study developed by AIARE education director Liz Riggs Meder and Eastern Oregon University Professor Kelly McNeil, gave quantifiable evidence to support the role of education in overcoming the human behaviors Fongemie, Trover and many other snow scientists and avalanche educators warn against. A backcountry skier and specialist in behavior change theory, McNeil questioned the avalanche industry’s dependence on snow science, saying, “Humans are the problem. Why don’t we use human behavioral research?”

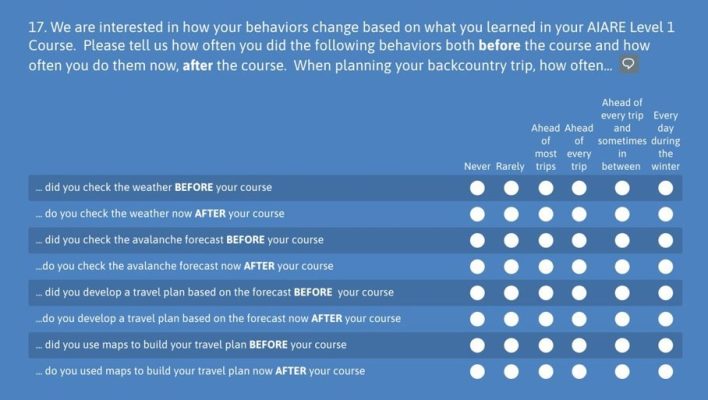

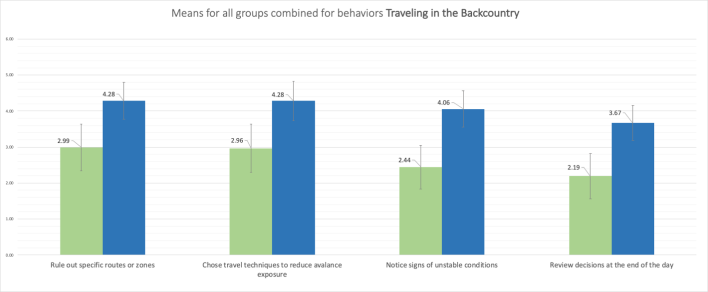

Surveying three populations of AIARE students—one population six weeks after completing the class, another one year after the class, and a final one two years after the class—researchers evaluated the effectiveness of avalanche education by measuring each group’s pre- and post-course behaviors. The survey asked questions about behaviors researchers identified as having the potential to increase the likelihood of good decision-making in the backcountry: Did you recognize any avalanche terrain? Did you do a trailhead check? How often did you do that behavior before taking the AIARE class and how often do you do that now after completing the AIARE course?

Looking at the data, Meder and McNeil found that, statistically, skiers perform these behaviors in the backcountry more frequently after taking an avalanche education course. For McNeil, it’s not just about safety. “Avalanche education is public health,” she says, and the data from AIARE’s study validates her point.

Whether it’s a community-based preseason discussion or nationally focused research, the importance of continuing to investigate how we educate people about snow safety is crucial to the sustainable growth of safe skiing and riding in the backcountry. Winter may have started dry, but with recent snowfall, avalanche danger, and sadly, incidents, have quickly risen.

It’s always a good time to buckle down on your own education in snow safety, and as the snowpack in New England develops, I’m excited to continue learning how I can implement safe behaviors while touring, even if my uphill playground is limited, for now, to local resorts only.

To learn more about the latest gear, trends and courses furthering avalanche safety, subscribe to the untracked experience. For more information about AIARE’s research, click here.

Related posts: