For painter Lori LaBissoniere, her artwork and environmental ethos go hand in hand. Through her work on reclaimed wood, she depicts the remote landscapes of the Pacific Northwest that she loves and her feelings about environmental degradation that are threatening her places of inspiration. We spoke to Labissoniere to learn more about her medium of choice and her artistic motivations.

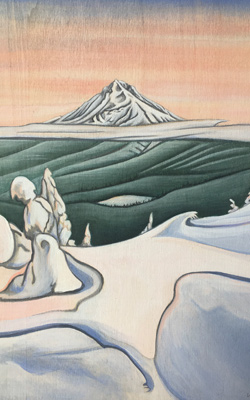

“Hurricane Ridge”

Backcountry Magazine: Tell me about you beginnings as an artist.

Lori Labissoniere: I live the life of a nomad—I’m all over the place. I grew up in Central Washington in Yakima. Ever since then I’ve lived all over the Northwest, mainly in Oregon, but my boyfriend and I just bought a cabin up north. It’s more remote and there are lots of mountains and lakes and my family is really close.

Since learning to snowboard when I was 16, the snowy mountains have been a huge source of inspiration. I love hiking in the summers too, as well as mountain biking, yoga and surfing. I used to surf more when I lived near the coast—I’ve done that pilgrimage a few times between the coast and the mountains—but I’m always drawn back to high peaks and views and remoteness.

I really like getting away from the craziness in modern society. I believe in helping to protect the natural areas that we have left in the Pacific Northwest, because the PNW is definitely being taken over right now. It’s just growing too fast. It scares me; it scares a lot of us, because we love these beautiful recreational sites and beautiful mountains and forests, but they’re being cut down and developed. Cities are getting bigger and stretching out. It is harder and harder to find solitude these days, and that is what I need to be inspired.

“Mt. Hood”

BCM: How has your style developed over the years?

LL: I always knew I wanted to be an artist, so I went to school for art. During my time at Gonzaga University, I wanted to study abroad, so I went to Paris and Florence to study art. That’s really where I discovered modern art. I grew up in a small town and was very sheltered, so I wasn’t exposed to all of the stuff going on today with art—I’d learned a little art history, but it wasn’t really until I did that trip that I saw artists in Paris making a living, even just off the street. I was inspired to think that I could do that too. It’s been a struggle ever since, but that’s why I became a teacher—to have something else to fall back on. And I feel pulled to help inspire today’s youth.

After I spent that time in Paris, I started studying all these different artists and began to develop my style. I’m really inspired by Japanese art right now and am trying to simplify my art as much as I can. I want to work more toward capturing the essence of nature instead of capturing every single little detail, and that’s why I like creating expressionist style landscapes. I don’t like just recreating a landscape and making it exactly like what it’s supposed to look like, because I don’t think you can ever really imitate nature like that; it’s just too perfect. So I like to put my own spin on things, and I like to work with wood grain—that inspires me too. It’s a natural surface, and I let the wood grain become the clouds or whatever I want it to be in the background.

“Tiny House Dream”

BCM: What got you started painting on the wood?

LL: I was part of an art collective in Bend for several years, and one of my studio mates—now a close friend—was painting on wood. She talked me into giving it a shot. At the time I was really frustrated with painting on canvas, because I was looking at this white, blank slate and just felt like, “Ugh, what am I going to do with this.” It’s not very inspiring to look at a blank canvas and think of something to do with it. Looking at wood grain—I can see something in it already without having an idea. But usually to get the idea, I need to go into nature and be inspired by something and either sketch or try to remember what I see.

I used to cover my wood pieces with resin, and I loved the way it looked. It had a shiny finish like a gem. But I realized that it’s so toxic and gross to work with, so I stopped. Now I use a lacquer coat or something like that. It doesn’t look as shiny, but it looks more natural, and I kind of like it.

“Driksen Derby 10 Board”

BCM: How does your environmental ethic play into your art?

LL: When I can, I try to find wood that’s reclaimed or reused. And then I build my own frames with the same kind of wood. And sometimes I need to buy wood because I need a nicer or more specific piece that’s bigger for certain projects I’m working on. But sometimes I’ll be walking down the street and there’s a construction site with a pile of wood that they’re going to throw in the landfill, so I’ll try to grab a piece and use that—plus it saves money.

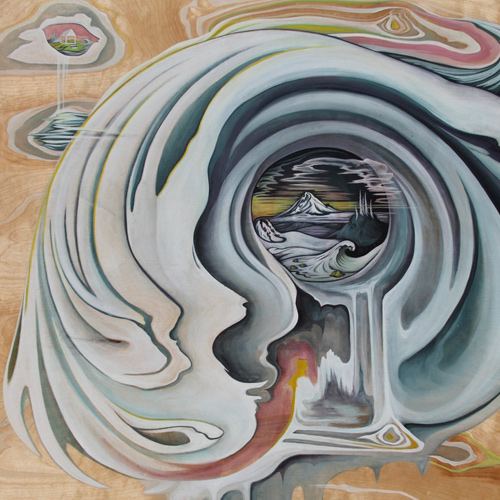

Sometimes I try to put messages in the art—I’ll have a clear cut or some kind of flooding or other anthropogenic impacts on the environment I’m trying to represent—an apocalyptic view of what’s happening with man vs. nature. I’ll also depict nature’s revenge. I was into that strong message for a while, and now I think I’m steering my art more toward simplifying and helping people see the essence of nature. I just want to help people connect on a deeper level with their natural surroundings in a more positive way.

LaBissoniere with deck art of her design. [Photo] Courtesy Lori LaBissoniere

LL: With the help of yoga, my boyfriend and some pretty gnarly injuries, I’ve learned to slow down a lot. In the past, I’ve tended to move through nature quickly. I’ll just go quickly on a hike or down a run and not stop and notice things. I’m learning the importance of more closely noticing my environment and being aware of how I make a turn down a mountain or a curve with my brush. I try to pause more so that I can remember what I’m seeing.

I just recently studied Sumi Japanese ink drawings; I taught a middle school class about it, and I learned a lot in the process. The Sumi artists learn to observe nature and sit in nature for a long period of time. Then, afterward, they take some ink and try to capture the essence of what they saw. It’s going to be what I want to do more of—maybe not so simple—but keeping that in mind.

“Noble Butte”

BCM: What does your process look like?

LL: I have to get out in nature and see new places to get ideas. Luckily, that is pretty easy to do in the Pacific Northwest. Recently, I’ve been visiting a lot of Native American cultural sites—important places that we’ve nearly forgotten about as a society. There’s this waterfall on the Columbia River, for example, that’s totally buried, because of the dams, and it used to be a really important fishing ground for Native Americans. It was drowned decades ago, and yet it’s rarely spoken about. So I made a painting bearing its name, Celilo Falls, with the waterfall buried below the surface of the water, the dam as a barrier between the fish and their spawning grounds. It is a metaphor for how we bury what’s happened in the past and ignore the pain it has caused to so many native peoples and species that once made this area so special. I try to tie in environmental themes that make people think and reflect on their relationship to nature.

“Ode to Celilo”

When I’m snowboarding, the views and the trees inspire me. It’s just so gorgeous when it snows. I feel really lucky that that I found snowboarding, because I realize how many people don’t get to be in the mountains like that and see fresh snow on a powder day. Everyone should get to see that. Hopefully my art reaches a few more people so they can experience what that feels like on some level.

—

See more of Labissoniere’s artwork at driftawake.com and her gallery at alpenglogallery.com.

Related posts:

Skintrack Sketches: B.C.’s former freeride competitor Richard Small on art, mixology and his native …

Skintrack Sketches: Mimi Kvinge looks to balance authentic artistic identity and brand

Skintrack Sketches: Artist Emma Longcope paints the public lands she protects by day

Skintrack Sketches: Vermont artist Jess Graham speaks to her love of lines in painting and snowboard…